The Ladakh Deployment: Soldiers Against Winter’s Fury

Sat, 16 Jan 2021 | Reading Time: 6 minutes

The Army Chief, General Manoj Naravane in his Army Day press interaction confirmed that the Indian Army is prepared to remain deployed in additional strength in Ladakh due to the current standoff with China. Sources also confirm that Indian Army units have adopted a system of turnover of the soldiers from absolute frontlines where both vigil and climate take a toll on their health, without any compromise in security. China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is also reported to have thinned out 10,000 troops from the depth areas to probably get them to more comfortable habitat in the rear. All this reveals just how challenging life can be at the high altitude areas along our borders and what it takes to defend them. There is much appreciation for the resilience of the Indian Army and considerable public interest to know more. The Army has not been expressive enough in the information domain to bring greater understanding of its challenges and needs to do more without compromising anything operational.

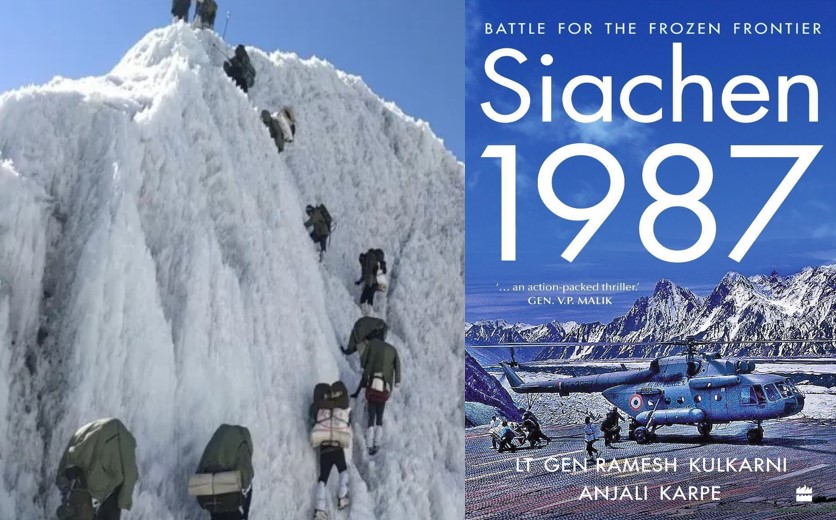

High altitude areas exist all along the border with China and in many areas along the LoC with Pakistan; the latter are in Siachen sector, Kargil, the entire belt of the Shamshabari and parts of the Pir Panjal range. With China, these lie in East Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarkhand, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. Each of these areas has its characteristics which have to be catered for in all planning and execution for a prolonged stay of troops lasting two years or more; that is the usual duration for an individual to live in these areas continuously. In the case of Siachen glacier, units remain deployed for six months excluding the time for reconnaissance, training, induction and de-induction. In those six months, there is one rotation so that no soldier remains deployed high up for more than three months.

There are ‘winter cut off’ posts, a phenomenon which probably no other army in the world has. It’s not the high levels of snow at the post but their tactical importance and the nature of routes which dictates whether they are declared ‘winter cut off’. If it is not possible to maintain these posts on a normal basis of sending up supplies, oil for heating and other commodities because of excessive snow on the routes and threat of avalanches, such posts are then classified as ‘winter cut off’ and remain occupied. The period of isolation may be as much as six months. It virtually means minimum 10-20 men being restricted to two to three shelters in a space of about 20-30 metres with a helipad some distance away reaching which would mean beating the snow, an arduous job by which snow is compacted to make it possible to walk over it. Most such helipads essentially remain limited to emergency supply or casualty evacuation. Every movement after a fresh snowfall or

the first time over a given route has to be preceded by snow beating to firm it. The speed of movement while doing this can be restricted to as little as a kilometre in six to seven hours. If the route is avalanche-prone the movement will be restricted only to hours of darkness when the snow is more firm. Interestingly preparation for such posts begins well in advance ensuring the selection of the fittest soldiers and officers, their psychological conditioning, leave management before they climb such a post, and various means of communication including STD facilities. It needs to be remembered that medical evacuation is next to impossible and no move of rations or any other material takes place in this period. Every item of necessity has to be stocked which includes burners for stoves and pins for cleaning them.

High snow levels at pinnacles and their vicinity pose multiple problems. I have risked authorizing a helicopter evacuation of a soldier suffering Acute Appendicitis from such a pinnacle in Uri with no helipad anywhere in its vicinity. The helicopter doors were removed and while it hovered the casualty was simply lifted and shoved into the rear and tied to the seat. At that height, the helicopter could not hover with the weight of another passenger who could have helped pull the casualty in and kept him secure. One of the worst incidents in my memory is of a soldier at a far forward isolated post who slipped on ice and fell headlong into 10 feet of freshly removed snow from a deep communication trench. He died since no one could locate him and he could not struggle out of the snow heap. The necessity of doing every chore with a buddy in tow prevents many such accidents. For even mundane tasks such as morning ablutions, it’s important to have a buddy with you, both keeping an eye on the other. Surprisingly, the people most vulnerable to falls and such vulnerabilities are unit cooks who are the first to rise in the morning and tend to work in isolation preparing meals at smaller posts.

Medical advisories force slow movement of personnel to the battle zone in high altitude. To serve at heights above 4500 metres soldiers have to first undergo two stages of acclimatisation lasting 10 days and four more at that height. Thus leave management, induction and relief of troops, as also transit infrastructure all becomes imperative. Acclimatisation helps the body to get used to the oxygen-deficient air and other peculiarities. However, it is not a guarantee against ailments such as High Altitude Pulmonary Oedema (HAPO). Other ailments can be enlarged heart or extreme cold-related ones such as Chilblain and Frostbite. A toothache at such heights and especially at winter cut off posts can be a misery necessitating elaborate dental checks before induction. Much depends on the precautions soldiers take based upon the quality of awareness and training. The wellness of troops is a command responsibility and a higher than usual percentage of ailments necessitating evacuation will be blamed on the command chain. Changing socks frequently, keeping feet and body dry from perspiration and consuming hot fluids in abundance are some of the measures advocated for better health. The challenge lies in ensuring discipline while deployed in penny packets in numerous posts. A single unit of 800 personnel could be deployed in 25-30 posts.

One of the old world adages is a blurb of the Border Roads Organization (BRO). It reads – ‘In the land of Lama, don’t be Gama’. I have never found a better reminder of the wisdom of the ancients. People who think they are as strong as the legendary wrestler Gama develop a sense of overconfidence which then becomes their bane leading to some deficiency in high altitude discipline. The blurb reminds you to be humble and not challenge the terrain. On one occasion I did go against this pertinent advice in Eastern Ladakh and learnt my lesson. I tried taking the long route in April to reach Leh from Tangse. The route Tangse-Chushul-Tsakala-Dungti-Nyoma-Kyari-Leh, in a year with a late winter when the traditional route through Changla pass was closed for a short while, was a veritable death trap. I had a flight to catch to attend the biennial conference of my regiment, the only one that I would ever attend as a Commanding Officer. In a single Jonga with tarpaulin flaps, no radio set and terrain in which no road could be seen we tried to make it. A Ladakh Scouts soldier guided us by smelling out the road through the whiteness of the snow. We made it in 16 hours to Kyari with life-threatening situations throughout, especially the drive over Tsakala on the Kailash Range, a post of great strategic significance today.

Siachen gets special clothing, mostly imported but all other high altitude areas get Extreme Climate Clothing or ECC; the quality of the latter is not anywhere near the imported clothing which is a pity, especially 60 years after the 1962 Sino Indian Conflict in which our troops had to fight without snow boots or even parka jackets. Where things have improved to a great extent is the rations and the quantum of fuel for warming and drying purposes. The severe challenge lies in their transportation to the last point of use. You need human labour (porters) and animal transport (ponies) which are usually locally hired and form considerable means of employment for the local people.

The implements for warming purposes are also archaic although improvisations work well. Modern devices such as LPG heaters are expensive and mostly bought from regimental private funds in limited quantities. The other big threat to life besides avalanches, extreme cold and altitude-related issues is incidents of fire. Fibre Glass Huts are warm and can be constructed quickly but are extremely flammable. The same goes with Snow Tents although heating them with single heating devices is comparatively easy.

Toilet facilities again pose a challenge with bathing usually very limited leading to problems of hygiene and sanitation. Waste disposal during winter and in Siachen even in summer becomes a major issue as space at posts is limited for waste disposal.

So even as 40,000 additional troops and equipment are deployed in Eastern Ladakh to meet the challenge posed by the PLA, people should be aware of some of the challenges and privations they suffer. As one of the most experienced armies in high altitude and glaciated warfare, the Indian Army has achieved a superhuman task of induction and being ready for any contingency in such a short time. May the Gods protect its soldiers from the travails of the terrain and the climate.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (12)

Dnyaneshwar Katkar

Shagun

Manohar

Tejas

Swapnil Dapkosh

Sudhanshu Sharan

SUHAS MISHRA

Brigadier S D Dangwal

Dr R Shankar

BN Sharma

P K Sengupta

Lekha Manohar