The Battle Of Thermopylae: One Of History’s Greatest Stands!

“Victory belongs to those that believe in it the most and believe in it the longest”

Randall Wallace

“No retreat, no surrender. That is Spartan Law. We will stand and fight….and die. A new age has begun: an age of Freedom! And all will know that 300 Spartans gave their last breath to defend it!”

King Leonidas of Sparta

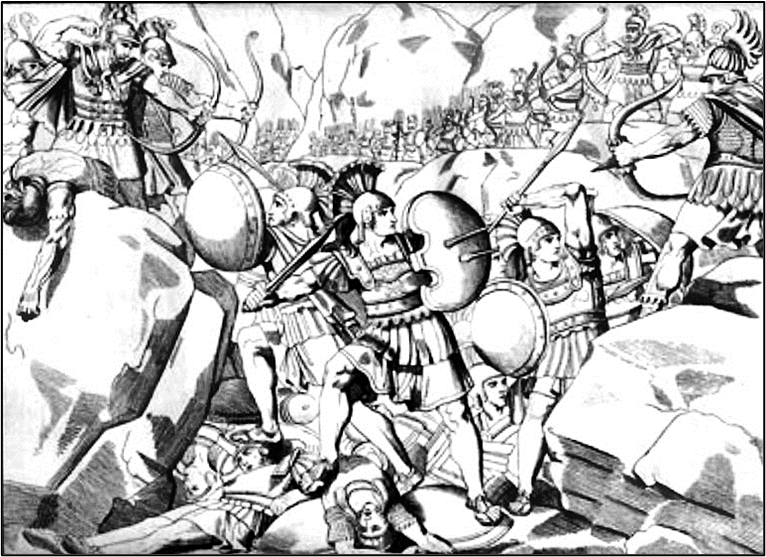

The battles of Longewala (Punjab- India vs Pakistan, 04-07 December 1971), Rorke’s Drift (South Africa: Anglo-Zulu Wars, 22 January 1879), Agincourt (France: England vs France, 25 October 1415) and Marathon (Greece: Greco-Persian Wars, 490 BCE) among others, all represent famous victories of a smaller force over a larger one. There are, however, other shining and poignant examples of last stands, when a numerically and logistically inferior force was eventually defeated by a larger Army, but not before inflicting significantly heavy physical and psychological losses that eventually provided a decisive turn to the campaign(s) in question. One shining example of such bravery, of which many annals have been written, is the Battle of Rezang-La in Ladakh, between soldiers of ‘C’ Company of 13 KUMAON and advancing Chinese forces, which led to almost the entire Company being martyred, but not before 1000 Chinese soldiers were killed, thus effectively leading to a ceasefire in the 1962 Sino-Indian conflict! This article will, however, attempt to profile an ancient last stand- the Battle of Thermopylae, fought 2500 years ago as part of the Greco-Persian Wars, by the Greek alliance led by Leonidas-I of Sparta against Emperor Xerxes-I of the Achaemenid or First Persian Empire, who had amassed one of the largest Armies the ancient world had seen!

Leonidas-1, Xerxes-1:Source-thefamouspeople.com

Such significant ‘last stands’ of numerically smaller contingents, many times with lesser wherewithal, over superior adversaries can be attributed to many causative factors- terrain, better training and equipment, preparation for battle (or lack of it on part of the superior force) and most importantly, the immeasurable qualities of bravery, espirit-de-corps and unmatched morale!

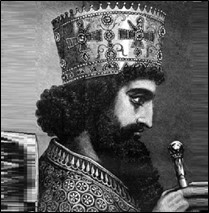

Source: worldhistory.org/WikipediA

Causus Belli & Prelude To The Battle

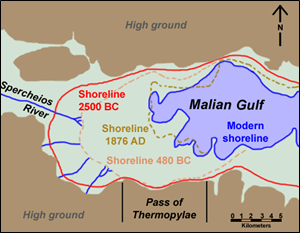

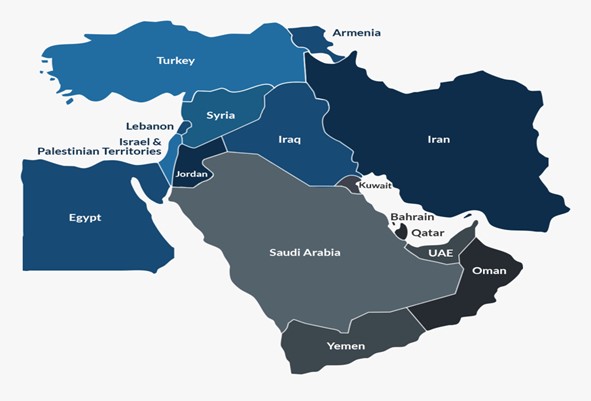

The animosity between the Persians and Greeks can be traced back to two decades before the Battle of Thermopylae, when the Greek City-States of Athens and Eretria provided support to several Greek regions of Asia-Minor in their revolt of 499-493 BCE against the Persian Empire of Darius-I. The Persian Emperor saw this as an opportunity to not only crush the rebellion, but also expand his Empire into ancient Greece. Darius’s emissaries asking for the Greeks to surrender were met with acceptance by most regions, except in Athens and Sparta, where they were executed. This resulted in Darius now considering both Athens and Sparta as his adversaries. A Persian expeditionary force was launched three years later, which first defeated Eretria and then engaged the Athenian Army at the Battle of Marathon, where the Athenians won an astounding victory despite being heavily outnumbered. This effectively resulted in the Persian Army of Darius-I withdrawing back to Asia. This humiliation led Darius-I to plan the defeat and subjugation of Greece with fresh determination, with deliberate planning, equipping and enhancing the Persian Army over the next decade. During this time Darius died, making his son, Xerxes-I, the Emperor. By early 480 BCE, the Persian Army once again advanced toward Greece. Meanwhile, Athens had also been preparing for this inevitable invasion and raised a large fleet of warships to thwart the Persian advance. However, the Greeks realised that they lacked the numbers to fight on land and sea and this led to the coalescing of an alliance of Greek City-States, led by the Spartans, which eventually participated in the Battle of Thermopylae. Once the Greeks received news that the Persians had crossed the Hellespont (the 1500-metre wide present-day Strait of Gallipoli in North-Western Turkey, between the Marmara and Aegean Seas and approximately 1000 Km to the North-East of Athens) on two pontoon brides (an unbelievable engineering feat at that time!), the Greeks, guided by the politician Themistocles, decided to adopt the strategy of blocking the Persian Army at the narrow Pass of Thermopylae, approximately 150 Km North of Athens and enroute to Southern Greece. As a contingency, any attempt by the Persians to bypass this route by sea could be thwarted by a Greek Naval blockade at the Straits of Artemisium (approximately 70 Km to the North-East of Thermopylae). The Battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium were thus fought simultaneously, with the latter consisting of a series of Naval engagements by the Greek warships against a gale-battered but superior Persian Naval fleet.

Map Showing Hellespont, Strait of Artemisium and Thermopylae: Source-Pinterest

The traditional Spartan Festival of Carneia, during which military activity was forbidden and the impending Olympic Games and consequent ‘Olympic Truce’, restricted the Greek Alliance from dispatching a large force to Thermopylae. Thus, only an Advanced Guard of 300 Spartans under King Leonidas-I was dispatched to defend the Pass. This force however grew in strength along the way and numbered about 7000 by the time it reached the Pass of Thermopylae. Leonidas chose to organize his defences at the ‘Middle Gate’, the center location out of three constricted areas along the Pass, where the Phocian Greeks had earlier built a defensive wall. This location had the Kalidromo Massif/Kolonos Hill to the left and the Malian Gulf to the right with marshy ground in-between and was therefore a suitable site (such was the defensibility of the site that British Allied Forces successfully defended the area against a Nazi invasion in 1941!). On learning that there also existed a narrow mountain path along the massif that could be used to outflank the Pass, Leonidas deployed about 1000 Phocians along the path.

Finally, the Persian Army was sighted across the Malian Gulf, advancing towards Thermopylae. Emperor Xerxes, knowing that Leonidas had occupied Thermopylae, sent an emissary offering the Greeks freedom and fertile land, which Leonidas refused. Xerxes then waited for another four days with his Army in the hope that the Greeks would surrender, before he finally commenced his attack on the Pass. The stage was thus set for the Battle of Thermopylae!

The Malian Gulf (now receded), 1m High Phocian Wall at the ‘Middle Gate’: Source- Wikipedia/ twcenter.net

The Kalidromo Massif as Seen From Thermopylae, Looking South: Source-Wikipedia

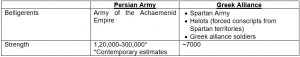

Force Levels

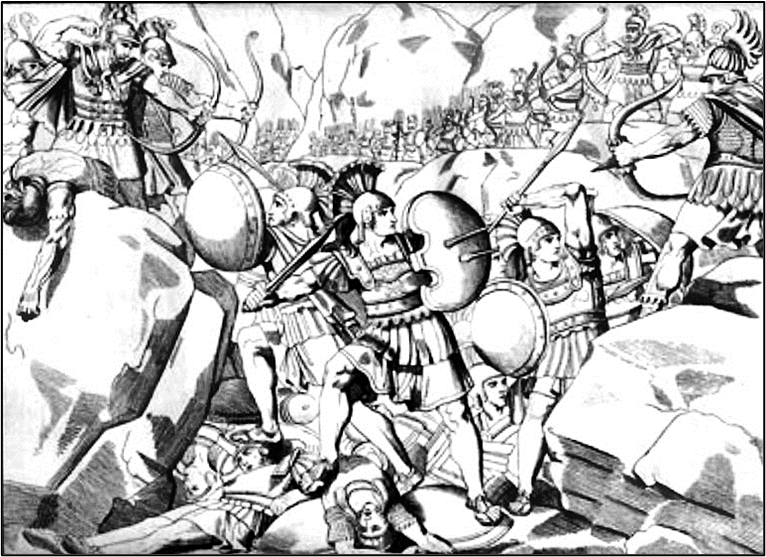

The Battle

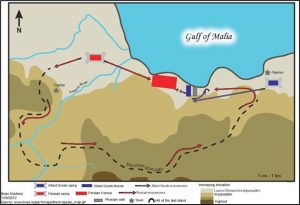

The actual battle commenced on the fifth day after the Persians had reached Thermopylae. The deployment on the Pass had the Spartans as the vanguard due to the narrow frontage available, with the rest of the Greek soldiers behind, who were in turn used as relief for the frontline soldiers.

Day-1. The Persian attack commenced with a volley of arrows from the Persian archers, which largely proved to be ineffective due to the sturdiness of the Spartan bronze-covered shields/helmets. This was followed by a 10,000 strong frontal assault. The Greeks met this advance at the Phocian Wall, with a Phalanx formation, standing shoulder to shoulder with overlapping shields and protruding, which decimated the Persian soldiers due to their weaker weaponry. Xerxes then dispatched 10,000 of his elite fighters (dubbed the Immortals), who met with a similar, albeit less severe fate, brought about by the Spartans’ tactics of feigning retreat and then attacking the Persians as the latter pursued them.

Day-2. Xerxes, assuming wrongly that the Greeks had suffered significant casualties, ordered his Infantry to attack the Pass, but they were once again beaten back. Luck later favoured Xerxes when a Greek named Ephialtes, in the hope of a reward, disclosed the mountain path that circumvented the Pass. Xerxes quickly dispatched 20,000 men, including the balance of the Immortals to outflank the Greeks there.

Day-2: Encirclement of the Pass by the Persian Army: Source-Wikipedia/livius.org

Day-3. At sunrise, the Phocians guarding the mountain path became aware of the outflanking Persian column and retreated uphill to fight. However, the Persians, not wanting to get delayed, shot volleys of arrows at the Phocians and continued their advance, thus effectively leaving the Phocians out of battle. Once Leonidas learned that the Phocians had failed to hold the path and that his force was in the process of being encircled, he announced to his soldiers that whoever wanted to, could leave. Most fled, leaving about 2000 loyal soldiers including the 300 Spartans to cover the retreat of those who had left. Xerxes once again ordered a mixed force of 10,000 Infantry and Light Cavalry to charge the Pass. The Greeks met the advance at the Phocian Wall, but were simultaneously attacked from the rear by the Immortals. A number of the defending soldiers were slaughtered and many surrendered, leaving a small force including the Spartans to fight to the last. It is believed that the defending forces used every weapon and means available in their last stand, in the end resorting to their hands and teeth! Xerxes then ordered this small defending force to be encircled and engaged with arrows, killing every last man including Leonidas!

The approximate losses/casualties suffered by both sides were:-

![]()

Aftermath

Since a successful two-pronged Greek defence hinged upon beating back the Persian Army at Thermopylae and defeating the Persian Navy at Artemisium, the fall of Thermopylae rendered the Naval operation by the Greeks irrelevant. The Greek Navy then retreated to the Saronic Gulf and employed itself in ferrying out Athenians fleeing in the face of the Persian advance. The Persian Army then proceeded to sack other towns that had resisted subjugation and finally reached and destroyed the now-evacuated city of Athens. The Greeks once again rallied at Corinth for a land-sea battle and this time the Persian Navy was decisively defeated at the Battle of Salamis. Xerxes then decided to retreat back to Asia across the Hellespont, fearing that the Greeks would destroy the pontoon bridges and leave his Army trapped in Europe. This proved to be the undoing of the great Persian Army and most of the force was devastated by starvation and disease on this return journey. The stay-behind Army left by Xerxes to complete the conquest of Greece was decisively defeated by the Greeks at the Battle of Plataea (South of Thebes- see first illustration) while the Persian Navy was routed at the Battle of Mycale (Turkey), both in 479 BCE, which effectively ended the Second Persian Invasion of Greece.

Source: Wikipedia

Significance/ Lessons

As mentioned earlier, the Battle of Thermopylae stood apart for the unmatched valour and loyalty shown by the Greeks and especially the Spartans in their last stand on the Pass. While this did buy some time for rallying Greek forces for further battles, it mainly deserves mention for the disproportionate casualties that the small defending force inflicted on the Persian Army, including the near decimation of their elite fighting Units. The selection of the site of Thermopylae and the Straits of Artemisium by the Greeks proved to be a strategic gamechanger, wherein optimal use was made of terrain to ward off a much larger force, while causing concurrent problems for the attacker to deploy and resupply large numbers. This author would venture to state that if the Greeks had not been betrayed, the Battle of Thermopylae could well have sounded the death-knell of the Persian land-advance into Greece! Selection of the Pass was also apt from the point of view of Greek Army tactics, which relied heavily on well-equipped foot-soldiers and tactical battle formations like the Phalanx in battle.

Conclusion

Battles, be they in today’s contemporary scenario or in the days of yore, have been planned based on optimal use of terrain, equipment and timing. Yet, many of these battles have stood out for the imponderables of valour, bravery, perseverance and grit. The last stand of the force at Thermopylae remains a lustrous example of a small force’s resilience in the face of overwhelming odds and unavoidable defeat.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (2)

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER