The Battle Of Hydaspes: Was It Ancient India’s Rubicon

GREAT BATTLES THAT SHAPED HISTORY

Geography has always been central to planning and conduct of battle. Indeed, ancient and even modern wars have been fought astride natural features or obstacles, with rivers enjoying rôle primordial in conflicts through the ages.

The famous phrase ‘Land of Five Rivers’ represents, for all intents and purposes, the fertile land of the Punjab, a part of pre-partition undivided India which transcended the frontiers of modern-day India and Pakistan. It was on the banks of one of these water bodies that the famous Battle of Hydaspes was fought in May of 326 BCE. And like the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back, Alexander The Great’s fourth battle in his expeditions through Asia, fought along the banks of the Hydaspes (the Greek name for the Jhelum River), proved to be his last in a glittering 13 year span of conquest, a conflict that brought him closer to defeat than ever before and laid down the limits of Alexander’s Asian campaign!

Causus Belli & Prelude to the Battle

There are many reasons attributed to Alexander The Great’s Asian conquest. These include (i) securing the maritime trade route through the Hellespont (a narrow, natural strait and internationally significant waterway that forms part of the boundary between Asia and Europe- a feat that even his father, Philip II, had not achieved (ii) securing the Aegean Sea, the water body between Greece and Turkey (iii) avenge the atrocities inflicted by the Persians on the Greek inhabitants in Asia Minor and secure their wealth (iv) be recorded in annals as the conqueror of Asia.

For eight years, since he marched out of Macedonia in 334 BCE in a bid to achieve the above, Alexander The Great moved like a juggernaut across Western Asia, invading and defeating the Achaemenid Empire (also called the First Persian Empire, which then included Egypt), in a series of battles ending in 328 BCE. Alexander’s success against Persia fuelled his ambition to advance his conquests towards India, which he is believed to have undertaken for a number of reasons. These included the fact that the Eastern reaches of the Achaemenid Empire also covered parts of the Indus River Basin- then represented by ancient India and therefore Alexander considered his Persian conquest incomplete without capturing the latter; also that in Alexander’s opinion, India represented the extremities of the Asian continent and successful invasion of India would represent culmination of his Asian conquest. Be these as they may, Alexander’s heart and mind were firmly set on conquering the Land of the Indus.

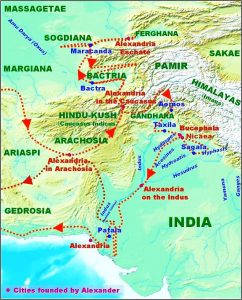

In 327 BCE, post his Persian conquest and after securing Bactria (a region North of the Hindu Kush Mountains which currently makes up the Central Asian Republics), Alexander’s Army advanced through the Khyber Pass (KP), a mountain pass across the Spin Ghar Mountains in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province in modern-day Pakistan that connects Kabul and Peshawar. The pass, a choke-point, is part of the ancient silk road and an eminent trade route between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent and has historically been witness to invasions of the Indian subcontinent from the Northwest. A smaller column under Alexander himself circumvented the KP from the North and captured the rocky fortress of Aornos, modern-day Pīr Sarāi, a steep ridge a few miles West of the Indus River and North of the ancient cities of Taxila or Takshashila (famous as the home of one of the world’s earliest scholastic universities) and Attock in modern-day Pakistan’s Punjab Province. This was Alexander’s last successful siege before he died in 323 BCE, wherein the numerous tribal clans of the Hindu Kush posed him stiff resistance, which his advancing column overcame, despite being heavily outnumbered.

Alexander’s advance over the next six months brought him West of the Jhelum River where he sent out a clarion call to the vassal rulers to profess their subjugation to him. Consequently, Alexander gained control of the Greater Gandhara Region (made up of modern-day Peshawar and Swat River Valleys in Pakistan), part of the Achaemenid Empire which also included Taxila. Alexander befriended Ambhi, the then King of Taxila- a pact driven by their common enmity for King Purushottama (popularly known as King Porus), the ruler of the Paurava Kingdom of Western Punjab, who refused allegiance to Alexander and instead was preparing to militarily confront the great Greek conqueror. The Jhelum River, as would be the Rubicon to Julius Caesar 277 years later, came to represent a point of no return for Alexander and Porus- Alexander had to comprehensively defeat Porus and decimate the latter’s Army to ensure his conquest further East and obviate a threat to his flanks, as also to send a clear message by way of a decisive victory, to the vassal Kings that disloyalty to Alexander’s cause would be met with similar ruthlessness. Porus, on the other hand, hoped Alexander would have to either wait for the monsoon season to end before crossing or simply abandon his quest and leave. For Porus, the battle was existential, as he needed to defeat Alexander to protect his kingdom. In preparation for the Macedonians’ arrival, he stationed his army in a defensive position along the Jhelum River and waited. And so was set the stage for one of the most decisive battles against a foreign invader that India has ever witnessed.

Alexander The Great’s Asian Campaign: Source-Wikipedia

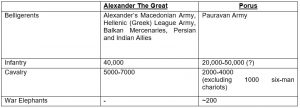

Force Levels

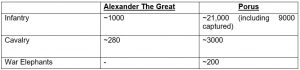

The force levels that faced each other at the Battle of Hydaspes are enumerated below:-

The Battle

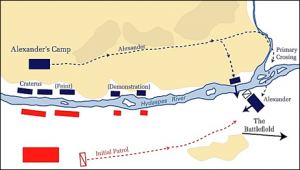

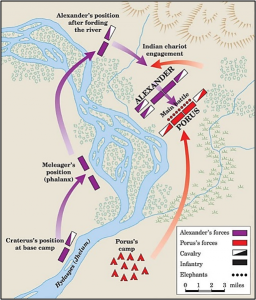

The opposing forces were arrayed on opposite banks of the Jhelum River, with Alexander setting up camp in the vicinity of a ford and Porus’ forces positioned across. Alexander was aware that the Hydaspes was deep and fast-flowing at the site of the opposing camps and therefore any attempt to cross it other than at a fording site would be perilous. He therefore made forays up and down the far bank, causing Porus to react by positioning and re-positioning his forces to thwart any attempt by Alexander to attempt a crossing. Alexander eventually scouted a crossing 27 Km upstream from his camp, at a place called ‘Kadee’, where the river was interrupted by an uninhabited, wooded island, which would act as an ‘anchor’ for his wading troops. Alexander divided his forces, leaving a substantial contingent with Craterus, his most loyal Macedonian General, facing Porus on the original ford, while Alexander led the rest of his Army consisting of approximately 6000 Infantry soldiers and most of his cavalry across the ford at Kadee. Craterus was ordered to ford the River if presented with an opportunity and attack if Porus repositioned his Army to face Alexander OR to hold his position if Porus faced Alexander with only part of his forces. Leaving behind a significant force at the original ford proved to be a masterstroke, which deceived Porus into thinking that Craterus’ contingent still represented Alexander’s main effort. What resulted was a pincer movement in which Alexander could attack Porus’ flanks, with smaller forces staging demonstrations and feints of attempts to cross the River at various points, thus dividing Porus’ attention and causing repeated decision dilemmas for the Paurava King. On receiving news of Alexander’s crossing being underway, but unaware of the force levels involved, Porus sent a small force under his son to thwart the former, which only resulted in the latter’s defeat and his death.

Porus, now aware of the crossing, re-balanced his forces to meet Alexander, with his heavily armoured war elephants evenly spread at the head of his force, followed by his Infantry, with his cavalry forming the flanks. Alexander seized the initiative, using his Dahae (Iranian) horse-mounted archers to decimate one flank of Porus’ cavalry, while the Macedonian Cavalry rode in to finish the task. Alexander’s Infantry then engaged the war elephants, which were proving insurmountable for his cavalry as the tuskers were startling the horses. Within no time the Pauravan Infantry was surrounded and routed by the Macedonian foot soldiers, who sported better armour and more lethal spears.

In the dying stages of the conflict, Alexander, impressed by Porus’ bravery, sent numerous emissaries including Ambhi, the Taxila King to Porus, asking him to give up battle, but the latter refused. Eventually, post the rout of his Army, Porus was brought to Alexander, who asked the former how he wanted to be treated thereinafter. To this, Porus famously replied “Treat me as a King would treat another King”.

The Battle of Hydaspes Showing the Rival Camps, Location of Fording Site and Broad Orientation of Forces: Source-Wikipedia/ warfarehistorynetwork.com

The losses/ casualties suffered by both sides are enumerated below:-

Aftermath

While Porus was defeated in the Battle of Hydaspes, Alexander, as a tribute to the former’s bravery, allowed him to continue governing the lands of the Pauravan Kingdom as a Satrap (Greek for Governor) of Alexander. Alexander, after instituting Porus as his representative, continued his conquest Eastwards, bringing him closer to confrontation with the Nanda Empire of Magadha, which was spread astride the Ganges River. During his advance Eastwards, the Macedonian Army learnt that the Nanda Army was reportedly five times larger than their own. Further, the Macedonians learned that the Ganges River itself was a far more formidable obstacle, with a rumoured ‘width of thirty-two furlongs’ (greater than 6000 m) and ‘depth of 100 fathoms’ (183 metres). Both these factors caused significant uneasiness in Alexander’s ranks, till, at the banks of the Hyphasis ( River Beas), they refused to march any further and demanded that they return back. Alexander eventually relented and turned Southward, advancing through Southern Punjab and Sind Provinces of modern-day Pakistan to the lower basin of the Indus River and installing Satraps in Multan, Punjab and the Indus Basin, among others, before finally turning Westwards to head back to Greece.

Significance/ Lessons

Alexander’s victory at Hydaspes was singularly significant as it opened the doors of the Indian subcontinent to Greek socio-cultural influences, including Greco-Buddhist Art, spawned from the combined influence of Macedonian and Buddhist culture from Alexander’s campaigns. The recording and archiving methodology of the Greek historians also proved beneficial in archiving ancient India’s history thereinafter. Alexander’s pardoning of Porus also gave a fillip to the former’s image as a compassionate and empathetic ruler, thus allowing acceptance of Greek culture for a long time post his campaigns.

Militarily the battle was significant for the vindication of the need for extensive preparation for battle in terms of strategy, tactics and wargaming contingencies. Alexander’s battle procedures which included multi-pronged attacks, coupled with deception achieved through concurrent feints/ demonstrations, influenced the campaigning philosophy of even the Mauryan Empire, wherein Kautilya studied this battle for its many military lessons.

Conclusion

The Battle across the Hydaspes would enjoy pride of place as a watershed event for a multitude of reasons, from the advent of the Greek culture into Southern Asia to the rethink that it spawned in military strategists and tacticians in the art of prosecuting war.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (8)

R Singh

R.Singh

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

Kalidan Singh

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

Girish

Lalit Saigal

Sh Sabh