It’s Not the Job of the Quad, Keeping Chinese Tankers Safe !

In mature democracies, the relationship between the foreign service and the Navy is symbiotic, with each service wishing the best of health to the other. In India, the relationship started off on a bad footing, with the then Indian political thinkers having unpleasant memories of being colonized by the girdling, aggressive British Royal Navy.

Indian ship visits were kept to a minimum and joint exercises limited to the navies of commonwealth countries – which intriguingly included the Pakistan Navy. These annual affairs were massive in scale and largely satisfied the British ego of the C-in-C Far East Fleet in Singapore. That we failed to capitalize on our enthusiastic participation was witnessed when our government’s request for modern submarines was turned down by a backward thinking British Admiralty.

A furious YB Chavan, the Defence Minister took a massive delegation with him to Moscow, where the suave Gorshkov opened the flood gates of Soviet weaponry to New Delhi. Thus began the great era of Indo-Soviet friendship spurred by a bunch of unread Admirals in London.

The downside of the induction of Soviet weaponry, ships and aircrafts was that India withdrew from the commonwealth naval exercises, which collapsed anyway, when a declining Britain withdrew all its forces from East of Suez. Unfortunately, the Indian Navy went into a shell and grew ignorant of naval developments in weaponry and tactics worldwide. This continued for 26 years until the end of the cold war.

In 1992 New Delhi responded positively to a diplomatic feeler from Canberra and agreed to the first bilateral naval exercise in a quarter of a century. Thereafter, it was all positive news, with the first visit of the US C-in-C Pacific to Naval Headquarters in Delhi and the first of the Malabar series of Indo-US naval exercises. Gradually, the Indian foreign office learnt the advantages of ‘naval diplomacy’, a concept that foreign office mandarins would have earlier laughed at. It was still difficult to push the envelope with the foreign office, in telling them that the naval textbook for the use of navies in ‘Less than War’ situations was authored by a British foreign service officer.

In the early 21st century, the number of bilateral exercises blossomed and the Indian Navy even helped some of the smaller navies in building up their tactical skills, as for instance, the Singapore and Omani navies in anti-submarine warfare procedures. The foreign office had finally grasped the significance of the use of Navy in diplomacy and Indian naval ships even visited New York for their national festival.

The foreign office had bitten the cake, but it was a very small bite. Naval strategists tasked with writing the Navy’s maritime strategy were often nonplussed as to how this could be done without co-opting the foreign office. For, after all we were discussing how to use force ‘outside’ the borders of the country. It was all very easy to define a land strategy by declaring a rudimentary territorial defence policy. Over the years, we even politicized this into some kind of ‘chowkidari’. But the subtleties of naval policy completely escaped the Indian politician, but attracted the attention of a few well-read diplomats.

The action of an alert and proactive Chief of the Naval Staff, who took the initiative of sailing every operational naval ship, on receiving the Tsunami warning elicited the admiration of even the most hide bound continentalist. It made the diplomats take the initiative in the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) and the Indian Ocean Regional (IOR) initiative. Half the battle was won.

In 2010, the Obama administration committed the big strategic blunder of trying to ‘co-opt’ Beijing into the world system, not realizing that the leadership of China would be taken over by a hardline Xi Jinping, who had far more ambitious ideas of world hegemony. It may sound bizarre, that at one stage, the Indian Navy even exercised with the PLA Navy in a fit of midsummer madness.

All in all, the foreign office had fully grasped the fact that the Navy is a powerful tool of foreign policy. In the meanwhile, two events were progressing side by side. The first was the realization in Washington, particularly after the 19th Party Congress in Beijing, that the US was in for a very long competition with Beijing, and that it could not be co-opted to play by the world rules of governance, without force. The other was that the US grand strategy required allies in Asia, as it once had in Europe, against the USSR. Obama’s pivot towards Asia and the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership, leaving Beijing out of it had all virtually collapsed. The only US initiative that seemed to offer hope was the re-entry of Australia and the formation of the Quad. Its beginnings were diplomatic and humble. The capitals of the Quad gave the clarion cry of ‘a shared vision of a free and open’ Indo-Pacific.

This was a good beginning, but hardly a strategy that would influence the choices available to Beijing. Sure enough, China spoke of the Quad in disparaging terms, that it would ‘dissipate like foam’. This was the time to transit the Quad strategy from diplomatic to military. But having learnt one lesson over three decades, the diplomats were being bone-headed about the basic function of navies. Agile thinking was not their forte.

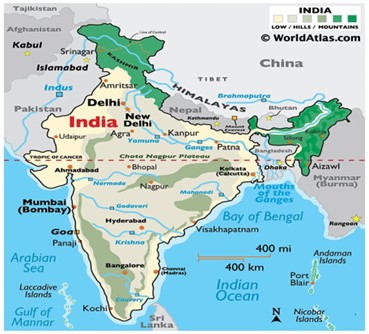

In June 2020, the Chinese bared their fangs at New Delhi in Galwan, and questions began to be asked as to what the Indian Navy could do. The question caught many strategists off guard, but not this author, who readily perceived that the great naval strength of the Quad lay in the large Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA) numbers with all Quad navies. It became crystal clear that by dividing the Indo-Pacific into areas of maritime search responsibilities, the Quad could establish overwhelming Information – Dominance in the area. It has also been clear to any thinking naval officer, that China’s weakness is its naval geography. That while it matches the US Navy in the South China Sea, its huge oil imports in the Indian Ocean are woefully unguarded.

Here was the opportunity. Beijing itself is terrified of its Malacca Dilemma. Make it real ! Quarantine some Chinese tankers in the Indian Ocean, activate the P-8 aircraft of the Quad, establish Info-dominance and hold the PLA Navy hostage as they enter the straits to try and resolve the issue. Thereby they would be walking into a deadly trap- what the Army calls, a killing ground.

Instead, the foreign office, is stuck in the diplomatic rut, grand standing about the Quad, and trivialising its purpose into dealing with climate change and vaccine export. Here is the opportunity to threaten Beijing with dreadful consequences and the opportunity is being lost talking about meetings between Heads of State, inadequately briefed on the crux of the matter.

No one wants to go to war, but a bully like Xi Jinping can only be dissuaded by the threat of force. There are many ways of signaling that the Quad can easily be jump-started into a military alliance. Publicise national maritime search areas, for me; establish a Quad secretariat for another, transfer four more P-8 aircraft from US to India, via foreign military sales. Lastly, drop the grandiose ‘vision of a free and fair Indo-Pacific’. It is not the job of the Quad, keeping Chinese tankers safe.

********************

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (3)

Deepan Gill

V S

M.Hanumanth Reddy