Delhi Declaration-Forging a Consensus on Afghanistan

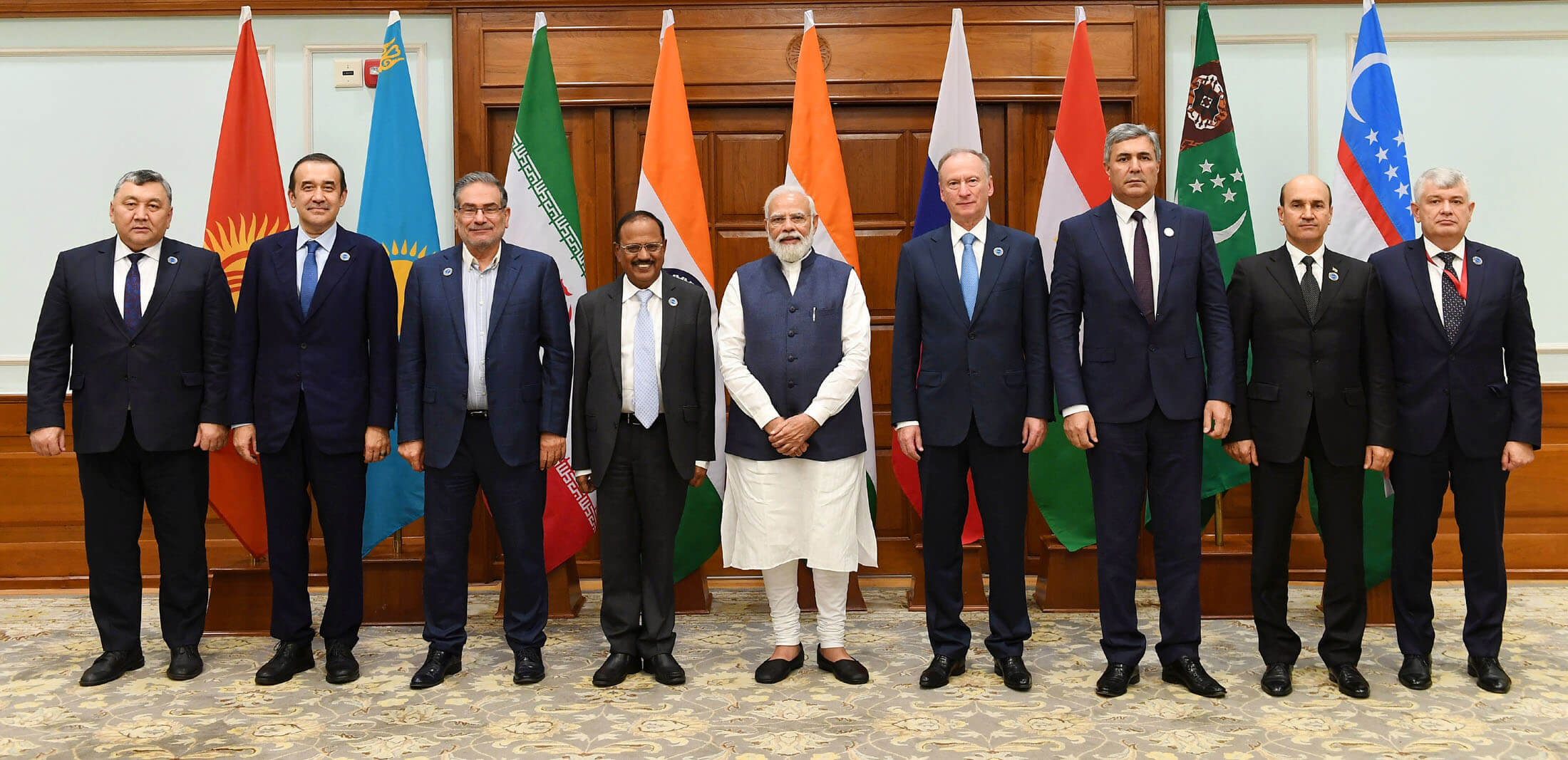

The meeting of the National Security Advisers in New Delhi on November 10 had multi-layered significance.

The initiative underlined India’s national security equities in Afghanistan. These equities are undeniable given the history of the subcontinent, the reality of terrorism and Islamic radicalisation in the region, the danger of conflict and instability in Afghanistan spilling into neighbouring states and the shared need to stabilise Afghanistan and ensure its independence and sovereignty.

These legitimate Indian interests in Afghanistan have not been given adequate recognition because of the Pakistan factor. Pakistan is seen as a crucial player in addressing the Afghan problem, not necessarily because its role is seen as positive historically. Its negative role in Afghanistan is recognised, but it is also recognised that without its cooperation no durable solution can be found to the turmoil in Afghanistan.

Pakistan has always frontally opposed India’s presence and influence in Afghanistan. To obtain Pakistani cooperation those countries wanting to play a leading role in promoting peace in Afghanistan have sought to either exclude India from the groups created for addressing the Afghanistan problem or avoid giving prominence to its regional role. One of the ways to exclude India has been to confine discussions to Afghanistan’s geographical neighbours alone.

India has also been in a bind with regard to active participation in negotiations on Afghanistan because of our unwillingness to engage and legitimise the Taliban.

The US has been primarily responsible for effectively excluding India strategically from Afghanistan by initiating negotiations with the Taliban at Doha with Pakistan’s assistance. Handing over Afghanistan to the Taliban-Pakistan duo presents India with a highly problematic reality. The stark failure of the Doha accord, the humiliating US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban reneging on the promises they had made on an inclusive government, the rights of minorities, women and children and not allowing Afghan territory to be used for terrorist activity, present the region with major problems ahead. The burden has fallen on regional countries to find a way forward.

It is in this context that our initiative to convene the meeting of NSAs should be seen. It is to assert our legitimate regional role and interests in Afghanistan. India faces in a sense the biggest security challenge in the region as we, unlike others, face a combined Pakistan-Taliban threat to our security, whereas the others have concerns about the spill over of radicalisation, terrorism, drugs and refugees into their countries.

Our initiative was timely as security concerns about the situation in Afghanistan have become paramount with the accretion of terrorist violence attributed to the Islamic State. This is evident from the fact that all Central Asian states attended, even those countries like Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan which are not contiguous with Afghanistan.

Russia’s presence was important because of its ambivalence about how much India should be involved in core discussions on finding solutions in Afghanistan, its support for Taliban as a legitimate political force and advocating that India engage with it. That the Russian NSA attended would indicate a change in thinking about developments in Afghanistan, concerns about the Taliban’s inability to control the situation, the internal conflicts that are building up and desirability of putting regional pressure on the Taliban to fulfil its promises. The US has walked out, and so it can no longer be blamed for the continuing turmoil within Afghanistan. Russia’s security agencies may now be making a different assessment of the situation in Afghanistan than possibly its diplomatic corps.

That Pakistan refused to attend has exposed its role and ambitions in Afghanistan. It cannot claim a constructive role if its paranoia about India is visibly dictating its decisions on Afghanistan. Pakistan may also have wanted to escape pressure on facilitating the flow of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan offered by India, which would have inevitably figured in the Delhi discussions.

The meeting of the regional NSAs in Delhi also signifies pressure on Pakistan to stay within the parameters of collective regional interest in Afghanistan’s future and not pursue policies dictated principally by its animosity toward India. The message is that Pakistan cannot have a free hand in Afghanistan and that regional balance and cooperation are needed. In this context Iran’s position is important, as it is deeply concerned about Pakistan’s role in Afghanistan. The meeting conveyed the message that Russia and all the Central Asian countries accept the legitimacy of India’s role and interests in Afghanistan in the security context. Beyond that it would no doubt be in the minds of the participants that stability in Afghanistan would require economic support, which India is in a position to provide now and in the years ahead.

China’s decision to absent itself in solidarity with Pakistan would have been rightly understood by participants as a gap between its professed role as a peace maker and geopolitical calculations directed at India. China’s absence and Russia’s presence has conveyed its own geopolitical signals. In the context of the Russia-India-China dialogue, SCO and BRICS, China’s decision to absent itself would not have gone unnoticed.

That the Delhi meeting could issue a substantive joint declaration on Afghanistan is remarkable. Forging a consensus is a diplomatic achievement. The declaration recognises the threats arising in Afghanistan from terrorism, radicalisation and drug trafficking as well as the need for humanitarian assistance. Emphasising the respect for sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity and non-interference in Afghanistan’s internal affairs can be seen as an allusion to Pakistan’s stated ambitions. India’s concerns are reflected in the emphasis in the declaration that Afghanistan’s territory should not be used for sheltering, training, planning or financing any terrorist acts, as well as the joint firm commitment to combat terrorism in all its forms and manifestations, including its financing, the dismantling of terrorist infrastructure and countering radicalisation, to ensure that Afghanistan would never become a safe haven for global terrorism.

The stress in the declaration on forming an open and truly inclusive government that represents the will of all the people of Afghanistan and has representation from all sections of their society, including major ethno-political forces in the country indicates that no formal recognition of the Taliban regime will be forthcoming until these imperatives are met. This also puts pressure on Pakistan which is lobbying for early recognition.

The declaration also underlines the need to provide urgent humanitarian assistance to the people of Afghanistan in an unimpeded, direct and assured manner and that the assistance is distributed within the country in a non-discriminatory manner across all sections of the Afghan society. This too is directed at Pakistan’s obstructive approach to India’s offer of food assistance to Afghanistan through Pakistan and lack of confidence in the Taliban regime in assuring that the assistance reaches all sections of society without discrimination.

While the results of the meeting need not be projected as giving India centre stage in the unfolding situation in Afghanistan as we go ahead, it should be seen as retrieving lost ground because of earlier group diplomacy on Afghanistan which de-emphasised India’s role and relevance. That the Delhi meeting was followed by a meeting in Islamabad attended by the US, Russia and China in another established format shows that countries will continue to explore various forums to address the very complex situation in Afghanistan that could not be solved with external military action and has to find an internal resolution with outside peaceful pressure and assistance. This is not going to be easy because of the nature of violent extremist forces that control Afghanistan and the equally, if not more, violent and extremist forces that oppose them from within. Solving the Pakistani problem, which neither the Soviets or the Americans could do, remains germane.

***********

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (1)

Kalidan Singh