Chinese Inroads into Nepal and its Effect on India’s Relations with Nepal

Mon, 30 Nov 2020 | Reading Time: 9 minutes

Part 1 – Historical Perspective & Sino – Nepal Relations

Nepal is a small country sandwiched between two enormously powerful neighbours, China and India, who are competing to become great global powers. Both countries have historically had very close economic and geopolitical relations with Nepal. Surprisingly, in the 18th and 19th centuries, Nepal was the most aggressive among the trio. King Prithvi Narayan Shah, who established the Kingdom of Nepal in 1767, compared Nepal to a ‘Tarul’ (a root vegetable) between two stones. He said that great friendship should be maintained with both the Chinese Emperor and the British to the South. King felt that the British was very clever and should be fought defensively and if found difficult to defend, persuasion, tact and deceit should be used (Muni 1973).

Coming into being in 1767, Nepal attacked and captured large tracts of territories of India and Tibet. British India pushed them back initially, but gifted large chunks of Indian territory in return for the help Nepal provided in quelling the First War of Indian Independence. In the case of Tibet, China came to their aid and put Nepal in a tributary relationship.

Relationship between independent India and Nepal became very complex, mainly due to India being a democracy and Nepal a monarchy. Democratic movements in Nepal were supported by India, leading to the ruling elites of Nepal having a constant feud with the Indian government. People to people relations were extremely good, with similar ethnicity and familial ties of the population on either side of the border. A large number of Nepalese soldiers fight under the Indian flag and are paid salaries and pensions by the Indian government. Hinduism and Buddhism also tie the two people closer. However, the ruling dispensations on either side view each other antagonistically. India baiting has become the most powerful election plank for all political parties in Nepal and the Indian government feels that Nepal does not respect India and appreciate the economic assistance and support for democratization provided by India. Nepal has also been exploiting the India – China rivalry, by playing one against the other.

In 1792, China brought Nepal into a tributary relationship along with Tibet, but Nepal stopped paying quinquennial tributes after 1908 when the Chinese emperor became weak. Peoples’ Republic of China and Nepal signed a boundary agreement in 1961 and thereafter their bilateral relations improved. China began investment in building infrastructure and Confucius centres in Nepal, especially close to the Nepal – Indian border. Nepal has also joined the Chinese BRI project. The economic relation between Nepal and China is likely to remain one-sided as Nepal is too small a market for China to make any worthwhile profit. Geographically, Nepal’s overseas trade is linked through Indian land route and ports. India is also Nepal’s largest trade and job market. China too can obtain optimum returns for their investments in Nepal, only if they get access into the Indian market through Nepal. For long periods in History, China treated Nepal as a ‘near barbarian’ nation, which should be controlled, to keep the Chinese periphery, stable and peaceful. In current times, it has changed, and China sees Nepal as a conduit to South Asia (Upadhya 2012).

China is very sensitive about ensuring stability and security in Tibet and political influence over Nepal is very important towards achieving this goal. China has been using a combination of economic incentives interlaced with aggressive diplomacy to secure influence over Nepal (Reeves 2012). Even though it is very clear that Nepal can augment economic development of Tibet, a few Chinese scholars have been highlighting the importance of Nepal as a ‘transit economy’ for China, opening up the markets of India and further to other South Asian countries (Zhengduo and Yan 2010). China can make substantial economic gains only if Nepal acts as a ‘transit economy’ and provide China with inroads into the very large market of India and rest of South Asia.

In 1910, China occupied Lhasa and the British did not have any objection to that, as they wanted China to act as a buffer to prevent the Russian Empire reaching India. In correspondence with the British, China referred to Nepal as a feudatory of China and in 1912, the Republican Government of China declared that Tibet along with Xinjiang and Mongolia was a part of China. Subsequently, Chinese General Zhang Yintang proposed to unify Nepal as one of the Five affiliated races of China. The Nepalese Prime Minister had politely declined the offer (Upadhya, Nepal and the Geostrategic Rivalry Between China and India 2012). In the 1940s, Mao had made plans to build a “Himalayan Federation of Mongoloid People of Tibet, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and India’s Northeast Frontier Agency” under China, but to no avail (Lama 2013). In 1939 Nepal was a ‘tributary’ of China, in Mao’s list and 1950, China’s declared objective after the liberation of Tibet, was Liberating Nepal (Muni 1973).

The first Afro-Asian Conference was held at Bandung in Indonesia from 18 to 24 1955, in which, many newly independent countries of Asia and Africa were represented. On the sidelines of the conference, Premier Zhou Enlai of China put forward a proposal to the delegation from Nepal for establishing diplomatic relations between China and Nepal. Subsequently, Nepal and China agreed to establish diplomatic relations based on ’Panchsheel’ or the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and it came into being on 01 August 1955. In the following year, they put ink to the Agreement on Maintaining Friendly Relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Kingdom of Nepal and the Agreement on Trade and Intercourse between the Tibet Region of China and Nepal (Sharma 2018).

The Agreement was signed at Kathmandu on 20 September 1956 and came into force for eight years, with the proviso to extend it with appropriate negotiations. The agreement made the bilateral diplomatic ties official and opened the doors for the establishment of trade posts in each other’s territories and open the borders for religious pilgrimage (China 2000).

According to SD Muni, the Agreement of 1956 had three standout features; re-affirmation of ‘Panchsheel’, Nepal’s recognition of China’s suzerainty over Tibet and it abrogated all old treaties that existed between Nepal and China. Nepal also had to give up all rights and privileges it enjoyed in Tibet in the past and had to withdraw her military escorts from Tibet. Conclusion of the agreement was followed by reciprocal visits by both prime ministers and a revival of cultural ties between China and Nepal. While all these were happening, Nepal continued to maintain its special relations with India (Muni 1973).

The treaty led to an improvement of Sino – Nepal relations and in addition, it gave Nepal a tool to counter increasing Indian influence within Nepal. China did not lose any time in initiating, what Narayan Khadka calls as “first aid diplomacy” by providing Nepal, grants and goods worth $12.6 million. Chinese inroads into Nepal led to the rekindling of Indian and US economic and security interests in Nepal. In 1956, the shares of aid coming into Nepal were, USA 59%, India 22% and China 8%. Chinese aid started growing after 1965 and by the mid-1970s, China was the second-largest donor after India (Khadka 1992).

Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1959, led to a large number of refugees crossing over into Nepal. This was followed by Chinese troops crossing over into Nepal to take action against the so called Tibetan ‘Rebels’, which forced Nepal to look for a boundary settlement with China, at the earliest. BP Koirala became the Prime Minister of Nepal in May 1959 and immediately proposed a boundary dialogue, which was accepted by the Chinese. Dr Tulsi Giri, a minister in the Koirala government visited China for a joint meeting in October 1959, but China did not play along and there came about considerable public pressure in Nepal for adopting a firm policy against China (Muni 1973).

BP Koirala himself led a delegation to China from 11 to 22 March 1960 and signed an agreement to resolve the boundary issue between the two countries. During the visit, the Chinese government also agreed to provide a loan for Nepal to construct a road connecting Kathmandu to Lhasa (Sharma 2018). Main features contained in the agreement on the “question of boundary between the two countries”, were as follows:-

- The boundary was to be scientifically delineated and formally demarcated based on the existing traditional customary line. (Art. I)

- The task of delineation and demarcation was to be performed by “a joint committee composed of an equal number of delegates from each side”. (Art. II) Broad guidelines for the committee were also laid down in the Agreement. (Art. Ill )

- “To ensure tranquillity and friendliness on the border”, the two sides agreed to demilitarize an area of twenty kilometres from the border on their respective sides. (Art. IV )

Koirala’s visit was reciprocated by Chou En-lai from 26 to 28 April 1960, during which a treaty of ‘Peace and Friendship’ was concluded. During Koirala’s visit to China in March 1960, he had proposed for the conclusion of this treaty of Peace and Friendship, in place of a Chinese offer of a ‘unilateral non-aggression pact’, which Koirala had politely refused to sign (Muni 1973). The Treaty was comparatively of less significance than the Treaty of ‘Peace and Friendship’, signed between Nepal and India in 1950, however, Chou En-Lai commented that it was political, with greater scope than the Treaty of 1956. The Sino – Nepal Treaty was a reiteration of ‘Panchsheel’. Main issues covered in the Treaty were as follows:-

- Settle mutual differences through peaceful negotiations.

- Develop and further strengthen economic and cultural ties for mutual benefit.

- Treaty was subject to ratification and was valid for 10 years.

Sino – Nepal Boundary Agreement

China and Nepal concluded a boundary treaty in 1961 (Nepal and China 1961). Article I (1) of the treaty says that,

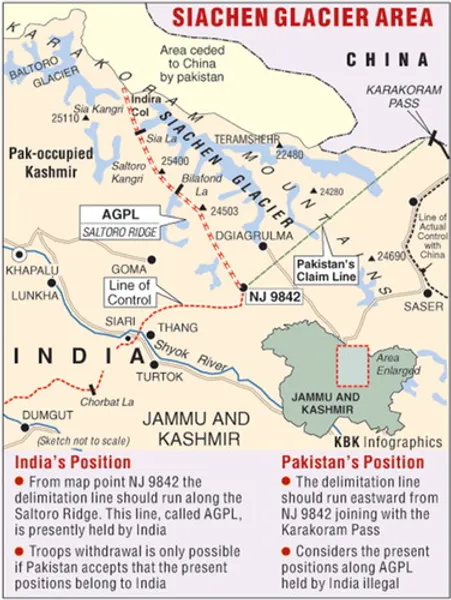

“The Nepalese-Chinese boundary line starts from the point where the watershed between the Kali River and the Tinker River meets the watershed between the tributaries of Karnali (Mapchu) River on the one hand and the Tinker River, on the other hand, thence it runs Southeastwards along the watershed between the tributaries of the Karnali (Mapchu) River on the one hand and the Tinker River and the Seti River, on the other hand, passing through Lipudhura (Niumachisa) snowy mountain ridge and Lipudhura (Tinkerlipu) Pass to Urai (Pehlin) Pass.”

The boundary line starts from the highest point on the watershed between Lipulekh and Lipudhura Passes. Origin of Kali River is shown to be at the Lipulekh Pass, written in Chinese and Nepali languages. This map was jointly prepared and signed as part of an international treaty by Nepal and China. A Joint Commission was set up to demarcate the boundary. The boundary was divided into six divisions and a joint team was dispatched to each to perform the demarcation work. In all, 99 boundary pillars numbered from 1 through 79 were set up along the boundary (China – Nepal Bou

ndary 1965), with Number 1 pillar at Tinker Lipu Pass (Cowan 2015). This confor

ms to the India – Nepal – China tri-junction marked on the Indian maps. In 1996, Nepal staked a claim to a portion of Indian territory close to this Tri – Junction, not taking cognisance of this boundary map jointly prepared by Nepal and China.

Map 1 annexed to Sino-Nepal Boundary Treaty of 1961. Kali River is marked in Nepalese and Chinese and shown to be originating from Lipulekh. Boundary marked on Indian maps given as green line.

There were a few vexing issues of dispute in settling the boundary, but China was magnanimous in understanding Nepalese sensibilities and made necessary accommodation. The boundary treaty did not mention the tri-junctions with India, on East and West of Nepal, as India was not part of the negotiations. However, the Chinese and Nepalese perception of the tri-junction conformed with the Indian perception, which was stated by Indian Deputy Minister for External Affairs, Mrs Lakshmi Menon in the Indian Loksabha on 16 March 1962. At almost the same period, China settled the boundary with Burma too, as if demonstrating to India that they were not averse to mutual adjustment of perceptions. China and India could not come to an understanding in settling their boundary at the same time and China probably wanted to blame failure on India. SD Muni believes that settling boundaries with neighbours was a strategy of China to make inroads into South Asia to enhance geopolitical influence and isolate India (Muni, Foreign Policy of Nepal 1973).

When a delegation from Nepal visited China in 1964, Mao referred to the Kathmandu – Lhasa road and told them that India may now be more respectful towards Nepal (Lama 2013). An anti-Indian bias was visible in the improving Sino – Nepal relations.

(Part 2 of the article will focus on the India – Nepal Relations and what do current trends indicate regarding the future of India – Nepal – China equation)

Works Cited

Muni, SD. 1973. Foreign Policy of Nepal. Delhi: National Publishing House.

Upadhya, Sanjay. 2012. Nepal and the Strategic Rivalry Between China and India. Routledge.

Reeves, Jeffrey. 2012. “China’ Self-defeating Tactics in Nepal.” Contemporary South Asia 20 (No 4): 525.

Zhengduo, Huang, and Li Yan. 2010. “China and Nepal Economic and Trade Cooperation: Present Situation, Problems and Counter Measures.” South Asian Studies Quarterly 67.

Upadhya, Sanjay. 2012. Nepal and the Geostrategic Rivalry Between China and India. Routledge.

Lama, Jigme Yeshe. 2013. “Securing Nepal in South Asia.” Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Issue Brief # 232.

Muni, SD. 1973. Foreign Policy of Nepal. Delhi: National Publishing House.

Sharma, Buddhi Prasad. 2018. “China-Nepal Relations: A Cooperative Partnership in Slow Motion.” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies 4 (3): 439-440.

China, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of. 2000. November 15. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/.

Muni, SD. 1973. Foreign Policy of Nepal. Delhi: National Publishing House.

Khadka, Narayan. 1992. “Geopolitics and Development: A Nepalese Perspective.” Asian Affairs: An American Review, Vol 19, No 3 (Taylor & Francis) 139-140.

Muni, SD. 1973. Foreign Policy of Nepal. Delhi: National Publishing House.

Sharma, Buddhi Prasad. 2018. “China-Nepal Relations: A Cooperative Partnership in Slow Motion.” China Quarterly of International Strategic Studies (World Century Publishing Corporation and Shanghai Institutes for International Studies) 4 (3): 443.

Muni, SD. 1973. Foreign Policy of Nepal. Delhi: National Publishing House.

Nepal, Kingdom of, and the People’s Republic of China. 1961. “Boundary Treaty Between the Kingdom of Nepal and the People’s Republic of China.” Peking, October 5. 1.

- “China – Nepal Boundary.” International Boundary Study (The Geographer, Office of the Geographer Bureau of Intelligence and Research) Study No 50 (Country Codes: CH-NE): 6.

Cowan, Sam. 2015. “The Indian Checkposts, Lipulekh and Kalapani.” The Record, December 14: 14.

Muni, SD. 1973. Foreign Policy of Nepal. Delhi: National Publishing House.

Lama, Jigme Yeshe. 2013. “Securing Nepal in South Asia.” Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies Issue Brief #232.

Hong-Wei, Wang. 1985. “Sino-Nepal Relations in the 1980s.” Asian Survey (The Regents of the University of California) XXV (5): 514.

Muni, SD. 1992. India and Nepal: A Changing Relationship. Delhi: Konark Publishers Private Ltd.

—. 1992. India and Nepal: A Changing Relationship. Delhi: Konark Publishers Private Ltd.

Mulmi, Amish Raj. 2020. “What does China want from Nepal.” The Kathmandu Post, November 19.

Jose, Jelvin. 2020. Commentary 5387, Kathmandu: NIICE.

Ghimire, Yubraj. 2020. Nepal-India Relations: A View from Kathmandu. Neighbourhood first series, New Delhi: Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (1)

Vinod Kumar