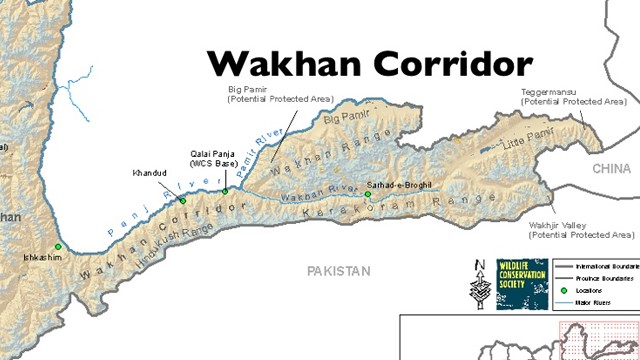

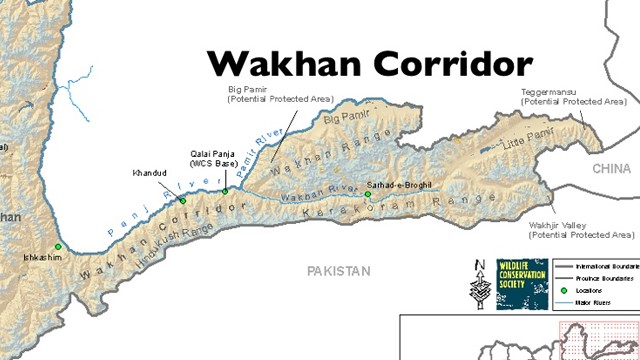

There have been widespread talks and increased curiosity about Pakistan’s plan (now aborted) to annex the 350 km long and 13–65 km wide Wakhan Corridor from Afghanistan.

Pakistani analysts have been churning out papers on the corridor’s historical, geographical, and strategic significance to unravel new opportunities for regional integration and connectivity with Central Asia.

Pakistan’s previous plan to cut over the corridor to reach Tajikistan was spurned by Hamid Karzai’s government. Islamabad anticipated that it would be simpler to armed twist the Taliban regime and quickly sent its forces into the Wakhan Corridor to erect pillars with signs “Pakistan 2021”.

Simultaneously, in July 2022, Pakistan officials contacted Dushanbe with a proposal to access Tajikistan via the Wakhan Corridor.

Abdul Khurram, Karzai’s former adviser, was the first to inform the Taliban about Pakistan’s sinister plan.

The furious Taliban quickly sent troops to pull down the pillars. The Taliban’s refusal to cede even one inch of territory to Pakistan has sparked controversy.

Pakistani officials have since been threatening to capture the Wakhan Corridor if Afghanistan continues to launch terrorist attacks on Pakistan. Pakistan’s airstrikes on TTP hideouts in Afghanistan and the visit by DG ISI General Asim Malik to Tajikistan on December 30, 2024, raised the specter of Pakistan seizing the corridor.

It seems that many Pakistanis have been experiencing imperial hangovers. They believed that the 350-kilometer-long panhandle was once part of British India and was created to serve as a buffer zone that is now irrelevant. Why not annex it? They reason that since Afghanistan hasn’t recognized the Durand Line, extending the boundary further north would be more advantageous to achieve greater depth.

They believed that now is the best time to conquer Wakhan because the world is focused on the Middle East and Ukraine conflicts, citing several recent antecedents, including Turkey’s occupation of Northern Syria, Israel’s occupation of Gaza, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and President Trump’s latest plan to revert to a “new Monroe Doctrine” to retake Panama, purchase Greenland, and unite Canada. Pakistan should capitalise on the unique opportunity that the world has not acknowledged the Taliban regime. This is another reason to act.

Pakistan has a long history of seeking strategic depth in Afghanistan. In the late 1980s, Zia- ul-Haq made the Americans and Saudis spend over $8 billion on the Afghan war, as part of a nefarious scheme to replace Afghan nationalism with a Pakistani brand of Islamic values. The ISI’s covert operation turned Afghanistan into a breeding ground for terrorists, displacing more than half of the Afghan population and leaving roughly one-third of the population dead.

The world was made to appear naive at that time. But Pakistan’s duplicitous plan has since been exposed.

To be cautious, Pakistanis tend to run with the hare and hunt with the hounds while simultaneously playing multiple games to seize a fresh opportunity to stir trouble in the region.

While Pakistan continues to advocate a diplomatic position that securing the Wakhan Corridor is critical to prevent the spread of jihadists from Afghanistan into China, Pakistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia as a whole, in reality, continue to use terrorism as a vital tool to advance their security interests in the region. The ISI retains mastery in managing terrorism, including transporting and training jihadists. Following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, the ISI has found a new way to play the terror game by instilling fear among its neighbours about the risk of terrorist groups emanating from Afghanistan.

The ISI employs terror as a means of deterrence and coercion against Central Asian states. To frighten Tajikistan, the ISI relocated the jihadists of Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), and others from Pakistan’s Waziristan to northern Afghanistan bordering Tajikistan.

Khawaja Asif, the Defence Minister of Pakistan, visited Dushanbe to assure Tajikistan about security cooperation.

The need to control the Wakhan Corridor has been factored into many Pakistani strategic calculations, such as advancing its CPEC and China’s BRI projects. Islamabad plans to use the corridor to expand its influence in Central Asia and impede India’s access to the region.

It’s an audacious idea for a bankrupt country to think about taking the Wakhan corridor from Afghanistan using force. It’s difficult to imagine how a superficial country could think, given that Pakistan is in illegal occupation of Pakhtunkhwa and Baluchistan, which are Afghan territories.

Pakistan’s own existence is hanging in the air. It is a failed state run by a corrupt military with an illiterate population begging on the street. A debt-ridden Pakistan will have to think about the repercussions of its actions.

When the Taliban demolished the Pakistani-erected pillars, villagers mocked the Pakistani military, saying, “We cannot expect Pakistan to defend Gilgit-Baltistan, which previously sold its land to China.”

Looking at the map, Pakistan looks to share borders with the Wakhan region, even though Pakistan is illegally occupying Jammu and Kashmir and has a 106-kilometer-long non-contiguous border with the Wakhan Corridor.

Wakhan was previously reachable by Chitral’s Broghul Pass, which crossed the Hindukush Mountain. The Irshad Pass connected Hunza to the Chupursan Valley and was used by traders from Kashmir, Ladakh, and Hunza.

The concern is whether China, which shares a 74-kilometer border with the Wakhan, will allow Pakistani military action. The Taliban constructed a route from the Wakhan Corridor to the Chinese border. However, China sees the region through a security lens and has a military post near the Tajik town of Shaymak, which is 30 kilometres from its border. If Tajikistan plays ball with Pakistan, it could risk dragging the country into a state of instability.

Wakhan is going to be part of Pakistan’s new intrigue, which could have unanticipated consequences. Gilgit-Baltistan, which borders the Wakhan Corridor, belongs to India; hence, New Delhi cannot remain a bystander.

Currently, the Durand Line is not a mutually acknowledged border. India should question the legitimacy of the Durand Line Treaty, which expired in 1993. The treaty envisaged Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s return to Afghanistan, analogous to Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997. Abdul Ghaffar Khan and other Khudai Khidmatgars refused to join Pakistan in 1947. As he felt betrayed, Khan wrote to Gandhi, ‘You have thrown us to the wolves.’ To play its own long game, India must engage with the Taliban to push for the de-recognition of the Durand Line.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (0)