Be careful of China’s Deception Tactics

The Chinese are masters of deception and denial is well known, for they see nothing illogical as being deceptive and talking of trust.

In 2016, to neutralise India’s position on Masood Azhar, Beijing raised some impalpable rules under the 1267 regime of providing “solid evidence” to prove his direct links with al Qaeda. While the “burden of proof was not on India”, Beijing tried to put India on the spot by invoking the “consensus” despite a “body of world opinion” supporting censuring Azhar.

China found no political sense to support India at the expense of Pakistan, especially when curbing the JeM activities risked stirring backlash against the CPEC investments. Instead, India’s pressures helped Beijing put more discreet demands on Islamabad to protect its assets.

A similar tactic was applied to block India’s NSG bid to get the 123 deal through. China termed it a “multilateral” issue and “it alone” isn’t blocking the bid. The issue was fudged while letting others push its case.

Through it, Beijing emphatically conveyed that Washington no longer holds the key to setting global agendas. Recall Beijing’s dig at Washington’s “outlier” comment – “NSG membership cannot be a farewell gift for countries to give to each other.” China expected New Delhi to consult with Beijing instead of seeking a last-minute discussion.

Perhaps, Beijing was willing to strike a deal provided India’s future policy trajectory is not aligned with America completely.

Ironically, China’s intractable views on arms control were shaped by US Ayatollahs. The Chinese non-proliferation experts equally reject the argument of India as “an exception to the case.”

India’s rise has never been comforting for China. While China considers India’s rise as a reality to push its businesses into India’s market it does the opposite by restricting India’s relative gains in the international system, thereby, creating doubts in the Indian mind.

The Chinese find India’s episodic fluctuations in its stance such as messaging through media rather confusing. Any deviation from the agreed mechanism amounts to an erosion of their trust. When former CDS Bipin Rawat remarked about China constituting the “biggest security threat”, the Chinese viewed it as a serious violation of the strategic guidance of the two leaders thus amounting to “inciting geopolitical confrontation, irresponsible and dangerous.”

The knowledge gaps and a lack of nuanced understanding of one another often cause discrepancies. As a result, the signals sent by one do not come out clearly to the other.

For example, any bumbling or bluffing attempt by India vis-i-vis China with empty threats without intention to back them up with actions could only draw a blank.

Even if the threats are honestly issued, they would be of no effect unless they are backed with credible actions or willing to pay political costs in case it has to back down. India’s ‘Tibet Card’ is being perceived as a tactic intended to provoke China with US support.

It isn’t that India and China made no moves for an upward spiral in ties. The Wuhan Summit was a serious attempt. In 2018, India’s DNSA Rajinder Khanna meeting with President Xi, and Chinese Public Security Minister Zhao Kezhi’s meeting with PM Modi entailed a substantive agreement on security cooperation, described by Chinese media as a turning point.

China wasn’t expected to budge on the NSG or Azhar case, but following the signing of a specific agreement and willingness to discuss issues internally through a well-structured mechanism made the difference.

Beijing refused to bail out Pakistan on the FATF. India, in turn, backed China’s bid for FATF Vice-Presidency. New Delhi reciprocated by curtailing the Dalai Lama’s activities.

India’s proposal for the UN Convention on International Terrorism (CCIT) got a shot in the arm when the 2018 Qingdao SCO meeting called for a comprehensive UN treaty on fighting international terrorism.

Indians expect that China should support India on counterterrorism given terror in Xinjiang holds validity if it doesn’t involve Pakistan. Recall, that India in 2016 refused visas to Uyghur leader Dolkun Isa to attend a conference in Dharamsala.

China applies a mix of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ policies in Xinjiang including strong social reform measures that if enforced in the Indian context would violate fundamental rights, besides facing the Western wrath over human rights.

China considers Xinjiang an ancient Sakas (Scythian) land that professed Buddhism of Kashmiri origin. Islam being a latecomer religion isn’t considered a legitimate basis for the Uyghur to secede from China.

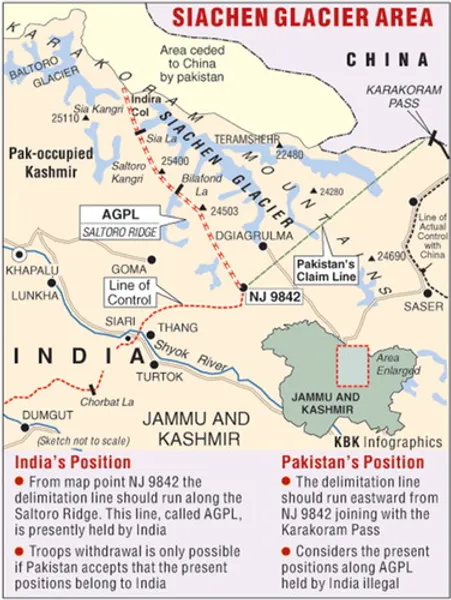

Strategic intent, not the boundary question underpins the nature of the India-China conflict, although, the border can create more flashpoints than the others.

The border issue has been a part of someone’s hatching strategy. L. Natarajan wrote that the ‘American shadow over the Himalayas’ started to loom large even weeks before Partition in August 1947. Border conflict is sequential and not the headspring of the mistrust. Sadly, it has descended into a vicious cycle of animosity and mistrust.

For now, the mode of diplomacy requires a change. Sending conflicting signals and playing shadowy games while using superfluous Cold War-era instruments do not squarely match China’s ability to destabilise India through other means.

India should not fall prey to provocation, for a national hysteria could again get hijacked for sabotaging India’s economic rise. PM Modi seems conscious not to repeat Nehru’s mistakes.

Reconciliation is a must but without compromising on India’s core interests. A dialogue process and a grand strategy are necessary not just for normalising ties but also to think more cunningly about gaining access to Chinese markets and reaching out to 800 million Chinese Dharma followers.

The Chinese also need to reformulate their thinking on the nature of India’s rise in the system.

The relationship can be transformed if we apply other methodologies based on “high-context” culture and communication enjoyed in ancient times. Only a top-down culturally moderated approach like the Wuhan process can remove the current state of relationship distress.

—

Author is a student of Eurasian and Inner Asian affairs

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (0)