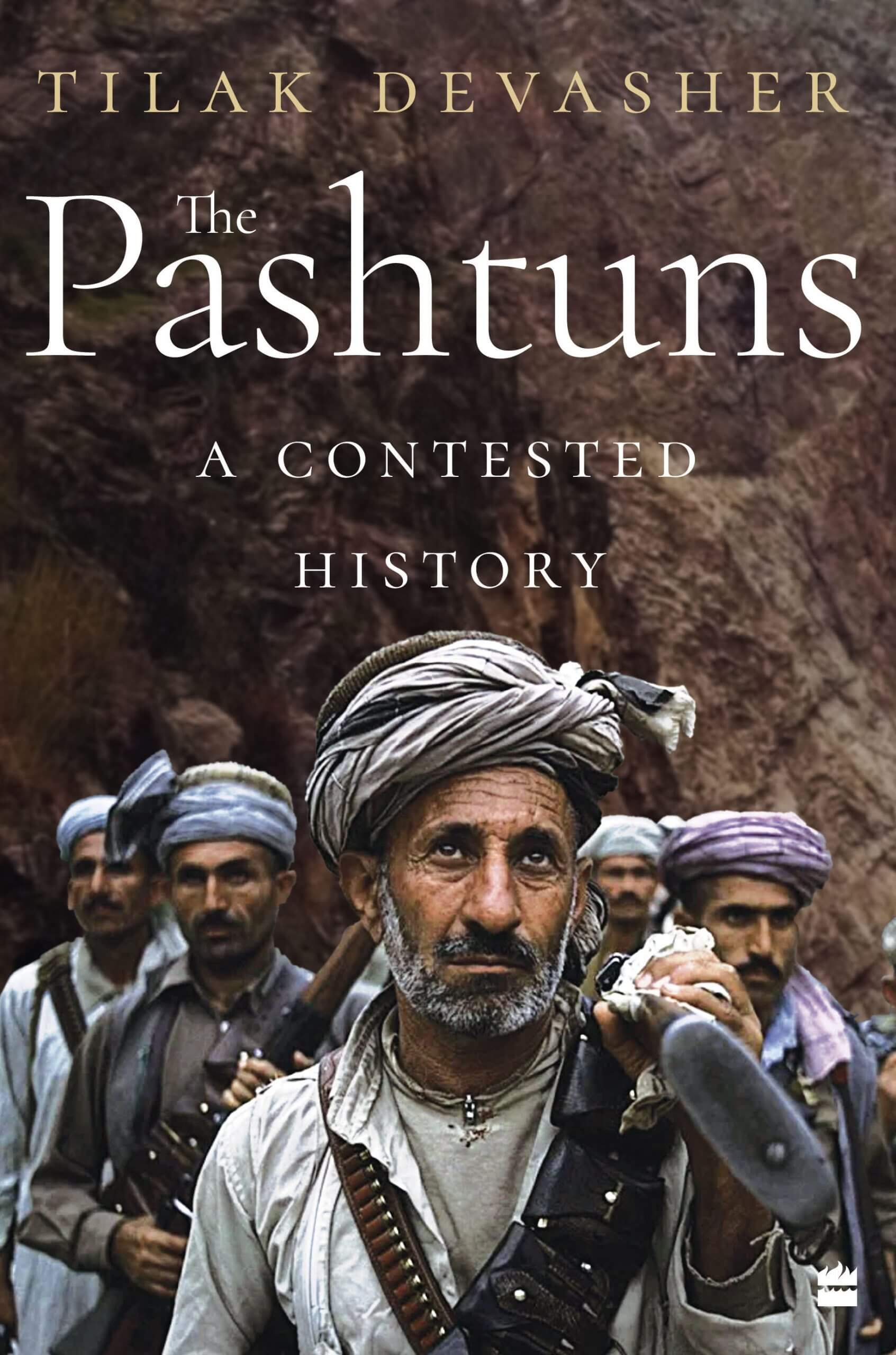

‘The Pashtuns: A Contested History’

Pashtunistan – the land of the Pashtuns- straddling an area of more than 100,000 square miles, historically stretches from the Indus to the Hindu Kush. Today, this land and its people stand divided by the British era controversial Durand Line into Afghanistan and Pakistan. Consequently, the Pashtuns, despite being the largest Muslim tribal population in the world, are without a state of their own.

Though divided between two countries, the Pashtuns share a common ideology of descent, a common religion, common ethnic, cultural, linguistic and familial bonds, common historical memories and a common code-Pashtunwali- the way of the Pashtun. These unifying bonds makes it possible to see them as a single entity inhabiting a single piece of real estate, distinct from their neighbours. Moreover, the present division of the Pashtuns is just one of the several avatars that this land has been subject to over the centuries.

Through most of history, the Pashtun region now included within the boundaries of Afghanistan and Pakistan has witnessed more invasions than any other in Asia, or perhaps the world. From the Aryans in about the second millennium BCE, to the Greeks, the Persians, the Sakas, the Kushans, the Hephthalites (White Huns), the Arabs, the Mongols, the Turks, the Mughals, the British and the Soviets, to the US, the region has perhaps seen it all. Uniquely, each time the invasions were motivated not by any intrinsic value of Pashtunistan in terms of resources or riches but due to geostrategic reasons. For millennia, landlocked Pashtunistan, located as it was at the crossroads of Central Asia, South Asia, the Middle East and East Asia, was the transit route to the riches of India. Most invaders attempted to conquer and subdue the Pashtuns but ultimately failed giving the land the moniker of ‘The Graveyard of Empires’. The reason was that, as all invaders found out, the Pashtun tribesmen would not be defeated. As has been well put:

You cannot defeat people who have no concept of defeat in the classical sense. They only believe in survival. They know when to fight, when to run and hide, and when to talk. Military operations against such adversaries can only have one objective: to bring them to the negotiating table.

Not surprisingly, these invasions have bred a tough and hardy people with a unique way of life and a unique way of looking at the world.

In medieval times, Pashtunistan was a borderland between empires that ruled from India, Iran or Central Asia. In the last two centuries, it has had the unfortunate distinction of being invaded by each of the great powers of the times: Great Britain in the nineteenth century, the Soviet Union in the twentieth and the United States in the twenty-first.

The tragedy of the Pashtuns is that since December 1979 they have been subjected to constant warfare. This prolonged war has caused one of the largest displacements of people in recent times, with the main victims being Pashtuns, whether they were refugees who sought shelter in Pakistan and Iran or the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) in Pakistan as a result of various army operations.

The Pashtuns have also suffered the most in the globalization of jihad because of the structural changes that Pashtun society underwent on both sides of the Durand Line. Traditional Pashtun leadership was brushed aside, at times violently, and replaced with Afghan and Pakistani radical Islamists. Worse, those being killed were Pashtuns and those who were killing were also Pashtuns. Most of the Afghan mujahideen were Pashtuns; the Taliban are Pashtuns; the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is Pashtun; those whom they have killed in Afghanistan and in the erstwhile FATA are Pashtuns; Even Pashtun children have not been spared. And the story is not yet over. The killings, the war, goes on.

Taking an overview, several strands about the Pashtuns will be visible in this book.

First, a major failing of the Pashtuns as a collective is that they have shown unity and national solidarity only when seriously threatened by foreigners. To a lesser extent, they, or a section of them, have also stayed united when engaged in successful military offensives, territorial conquests and plundering raids. Other than that, the long history of the Pashtuns shows fragmentation and feuds and conflicts with one another. Attempts at unity by some leaders have either been futile or have not lasted beyond the lifetime of the leader. As a result, outsiders have subjected them to intermittent invasions and even occupation, however limited in time and space it may have been.

The second strand is the representation of their proclivity for conflict and warfare largely due to excessive reliance on colonial literature. For example, as Winston Churchill wrote: ‘Except at the time of sowing and of harvesting, a continual state of feud and strife prevails throughout the land. Tribe wars with tribe… Every tribesman has a blood feud with his neighbour. Every man’s hand is against the other and all against the stranger.’

Unfortunately, there has been a lack of counternarratives about the Pashtuns that could challenge the colonial stereotypes. The non-violence of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan; the activities of Pashtuns tribal elders who have stood against the Taliban and al Qaeda and paid a huge price for such resistance and the evolution of the non-violent Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) have not received the kind of attention they should have. Apart from the lack of counternarratives, while there is an abundance of British literature on the Pashtun, there are not many Pashtun versions of how they saw themselves or saw the British. As Ghani Khan, Ghaffar Khan’s son, put it: ‘The Pathans have no written history, but they have thousands of ruins where the hungry stones tell their story to anyone who would care to listen.’

Third, a critical thread after the creation of Pakistan in 1947 has been the Pashtunistan issue. The newly created state of Pakistan inherited the British territories and with it the issue of Afghan irredentism. The efforts of Ghaffar Khan to unite the Pashtuns into Pashtunistan at the time of the partition of the subcontinent came to naught but it sowed the seeds of doubt amongst the Pakistani leadership about the loyalty of his followers. Post Partition, several Pashtun-led Afghan governments, intermittently raised the issue of Pashtunistan, about the validity of the Durand Line, and challenged Pakistan’s right to rule over its Pashtun areas.

For its part, Punjabi-dominated Pakistan has worked systematically to overwhelm Pashtun impulses for Pashtunistan. This central thread has been one of the key drivers of Pakistan’s policy towards the Pashtuns. Its efforts have been to snuff out Pashtun nationalism and install a friendly and dependent government in Kabul that has been mainly responsible for the current turmoil in Pashtunistan. To do so, Pakistan has manipulated the deeply held religious beliefs of the Pashtuns to encourage the growth of radicalism, terrorism and violence.

An interesting dynamic at play currently is how would a resurgent Taliban deal with the issue of the Durand Line. In their earlier avatar in the late 1990s, they refused to accept it despite Pakistan pressure. Current indications are that not only have they continued to resist such pressure but elements of them have actually torn down the fence in certain areas. The leadership has called the issue unresolved and termed it as dividing a nation. The moot question is if the Taliban will be able to further the issue of Pashtunistan and the aspirations and interests of the Pashtuns.

‘The Pashtuns: A Contested History’, seeks answers to questions like who are the Pashtuns, where did they come from, what are their social and religious beliefs, and what is Pashtunwali and its relationship to Islam? It discusses the British experience of a century of contact with the Pashtuns, the Durand Line, the developments in Afghanistan up to and including the Soviet intervention, the mujahideen, the civil war and the rise to power of the Taliban in the 1990s. It goes on to describe the US intervention, the Taliban resurgence and ultimate victory, the incubation of the al Qaeda and Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) and the dubious role of Pakistan in these events.

Finally, the book analyses the strengths and weaknesses of the Pashtuns and the role of the US and of Pakistan. If the Pashtuns are ever to find peace and tranquillity that they long for, break away from the cycle of violence and war, they will themselves have to find answers for their predicament and not depend on others to do so.

Despite their internal differences, despite foreign interference, and above all, despite Pakistan fomenting extremism in Pashtunistan to erode the Pashtun ethnic identity, this writer is convinced that sooner or later, the Pashtuns will rise above such attempts and re-assert their common ethnic identity on both sides of the Durand Line even more strongly.

As the Pashto saying goes:

Afghan Baqi, Kuhsar Baqi. Alhamdo-Lillah, Alhamdo-Lillah

[Afghans (i.e Pashtuns) and their mountains will keep standing, praise be to Allah, praise be to Allah].

*****************************

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (9)

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

Pranay Dhande

M. AZAM

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

SOUMYADIPTA MAJUMDER

Vikrant

Ahsan Ullah