Taliban – A Mentality Not an Ethnicity: A Ground Report from Afghanistan

Wed, 17 Feb 2021 | Reading Time: 12 minutes

India’s rejection of the US’ “good Taliban – bad Taliban” stance has been consistent. However, my interactions on the ground with the Taliban over a period of a few weeks travelling the length and breadth of Afghanistan have shown, that there is indeed a significant different division within the Taliban.That said, the US is also not entirely accurate in bifurcating the Taliban neatly into good-bad binaries. The problem is the “Taliban” are ordinary Afghans, whose normally tribal, warlike lifestyle has been carefully moulded by Pakistan into a comprehensive anti-government strategy.

The question is what would a correct understanding of the Taliban fault lines be? What can India do? And what lessons must we incorporate into our Afghan strategy?

Paying obeisance at the tomb of Ahmad Shah Masood in the Panjshir Valley

Background & Methodology

My visit to Afghanistan from March to April 2019 was divided into two parts. The first as a tourist and the second after much liaising with sources in both Afghanistan and Pakistan, as a study tour specifically liaising with the Taliban under the safest possible circumstances. While the intent was also to investigate the condition of women, these interactions in rural Afghanistan were exceedingly rare given local cultural norms. As a result, only 18 interviews of rural women could take place without male supervision.

While this report uses anecdotes, it is based on primary research as best can be conducted in a high-risk conflict zone, with anecdotal references used merely to highlight some of the conclusions. To note that while the primary research did involve a significant number of interviews, these had to be done randomly as the opportunity arose and could not be carried out as per age, religious, ethnic or gender demography – hence I have avoided tabulating the results.

Afghanistan

Landing in Kabul is one of the most thrilling experiences. Nestled in a valley, the approach is a corkscrew where the plane has to fly very close to snow-capped mountains. The problem is, having been brought up on a steady stream of how beautiful Kabul is from the Baburnama, Kabul has absolutely no charm. A massive swelling of the population due to the ongoing insurgency means the city has been turned into one big slum – if you live in Delhi – visualise Hauz Khas village minus the restaurants and pubs. Traffic is chaotic – but security outside the airport is relatively lax, till you come to the business heart of the city. Contrasting this with my experience of visiting Srinagar in August 2019, a month after the abrogation of Article 370, security is far stricter in Kabul, though more pervasive but lenient in Srinagar.

Kabul is a bustling city and there is significant freedom of movement as long as one is innocuous (dressed as an Afghan) and sticks to tourist locations. I was to discover shortly thereafter how easy it was for lower and middle-level Taliban functionaries to come into Kabul for meetings. Day 1 involved an obligatory trip to the bird market – where one can buy a wide variety of caged bird including trained eagles and falcons. The smell is disgusting, not to mention a serious health hazard. Thankfully the tomb of Babur made up quite considerably. What is still not understood is, what exact beauty Babur found even in his final resting place, with the backdrop of a formidable but arid hill and a generally arid landscape with patches of green here and there. The famed melons and peaches of Afghanistan too left much to be desired – a far call from the eulogies to them in the Baburnama.

Trips out of Kabul were extremely high risk and had to be aborted the moment the driver felt unsafe. Drivers and cars had to be hired anew every morning to ensure the driver of the previous day would not be used again (the Taliban pays people for delivering foreigner to them) and cars had to be changed so that people would not know which guest house one was staying in. The short fast drive to Jalalabad was the first introduction to driving in the Afghan countryside. Less than 30 kilometres outside town, armed men started appearing (on one occasion with a rocket-propelled grenade clearly visible) and some in large groups. The problem is one couldn’t tell if these people were Taliban or just normal armed Afghans. My guide found it amusing that I thought there was a difference. While there were no Taliban Check posts, what was curious was that the occasional US and ANSF convoys would elicit one of two reactions – the armed men would get radio communications and saunter out of view. Or they would simply stay right there, in full view and let these military convoys pass.

This 3rd day in Afghanistan was particularly insightful, because it showed both the impossibility of identifying “Taliban” but also the sheer futility, given how easily they blend into the population – because they are the general population. Jalalabad and the road approach to it were particularly heavily guarded that day and a mere 20 kilometres from the city, we were told to return as the “situation had become untenable”. Mind you this wasn’t just for us, but the entire traffic from Kabul was being diverted back due to a large counter-insurgency operation in progress. The sheer number of armed non-military men along the road now made perfect sense. Though what did not make sense was how neither US nor ANSF made contact with these armed men on the highway. It seemed quite clear that some tacit rule exists for “mutual tolerance” outside a “designated conflict zone”.

At a Local country fair in Samaghan

The next day involved a drive from Kabul through to the Panjshir valley, with a small diversion and stop-off at the historic Salang pass and tunnel. Panjshir is truly beautiful as is the drive north. Once you enter the stunning deep ravines you see exactly how Ahmad Shah Masood was able to hold off the Soviets for so long so close to Kabul. Unlike the harrowing drive to Jalalabad, this drive was relaxed, with lots of tea stops, interaction with locals and shopping for curios. The most amazing part of this drive is the sheer number of tank, IFV and APC wreckages one comes across. Literally every 100 meters or so one can see badly damaged T-55s, T-62s, T-72, as well as assorted BRDMs and BMPs. Curiously, while Soviet equipment littered the landscape, on the drive one was able to spy, neatly organised graveyards for damaged US equipment – mostly Humvees but a lot of assorted MRAPs as well – possibly to hide the extent of losses since the US invasion began.

One main factor was the inability to get drivers to go to certain areas. Not one single driver was found, despite a generous trebling of terms to drive from Salang onto Mazar-I-Sharif. That trip had to be done by air. Mazar itself felt just as unsafe as Kabul. While I had assumed the high Tajik & Uzbek populations would hold back a “largely Pashtun” Taliban, that was simply not the case. The culture shock of having been too heavily Europeanised Uzbekistan and Tajikistan the previous year was particularly stark when contrasted with the local Uzbek and Tajik populations. This is where you begin to realise, that the Taliban while mostly Pashtun, is not entirely Pashtun and seemingly enjoys significant support. A generic (and a totally unscientific straw poll conducted at and around the mosque) revealed that an overwhelming number of the Tajik, Uzbek and female respondents, actively supported or were neutral towards the Taliban. When I questioned further if in any way the Taliban threatened their ethnic identity, the almost reflexive answer was “we are Muslim, they did trouble the Shia but they don’t interfere with us”. The Shia respondents seemed mixed. The ladies who had headcovers (very few) detested the Taliban but it also turned out they were urban educated Shia women. Almost all the Shia women in hijab merely gave me variations of “they are patriots; if they leave us alone we will support them; these days they don’t interfere with us”

It was at this point that my overall tour guide, a Hazara, whose brother had been tortured and killed by the Taliban in 2000, asked me in a bewildered way “why do you think there’s a distinction between Afghans and Taliban?” He vehemently insisted that I should stop viewing this from us versus them, Pashtun versus non-Pashtun lens. His own (very perspicacious) explanation was that being Taliban was a “mentality, not an ethnicity”. The drive to the ancient fort of Balkh – the final place where Zoroaster lived, where Alexander’s bride Roxanne was reputedly born, and destroyed several times including by Genghis Khan and Timur, was particularly revealing. While Balkh is considered a “safer province”, it clearly is not. Our drive to Balkh was intercepted by several Taliban checkpoints. While they self-identified as the Taliban, the only thing they were interested in was collecting road taxes. A stop at the historic Nau-Gumbad mosque, built on a Buddhist shrine, which in turn was built on a Zoroastrian one brought the first unplanned interaction with the Taliban. I was convinced at this point that things were going to go south – especially when for the only time during this trip I had guns pointed at me. However, the mention of the magic word “Hindustan” calmed things down quite significantly, and I was invited into the hut of the caretaker, a sad figure who had lost his entire family during the war.

On the grounds of the mosque, he grew his crop of hash, which I was required to smoke when chatting with the Taliban. I soon realised why, the stuff was potent and loosens the tongue significantly, almost as if it were a truth serum. The conversation mostly hinged around how much respect these men had for India, and how projects by India had helped their family members directly. Surprisingly to a man they detested Pakistan. On being asked why they were fighting the government, not one single answer had anything to do with a “national cause” or hatred of foreigners. Of the nine men present, three had a personal vendetta against a local government official, one was there because of a family loss (his brother had been killed in fighting), and the rest were there for “family reasons” mostly as having been promised for good and services rendered to the family and it was subtly suggested partially through threats as well.

Herat was possibly the only city where the “central business district” was almost entirely unguarded and bustling. There were a significant number of women with a head covering but refusing to wear the Hijab. Importantly the Shia are visible and assertive, prosperity is visible on the streets, and there is a pronounced cultural affinity more to Iran than say Kabul. However, a drive out of Herat towards Ghor and the fabled Minaret of Jam brought home the reality of how close the fighting actually was. Of particular interest to me to trace the roots of Muhammad Ghori, but within about 1 hour outside heart one could hear the distinct and unmistakeable din of gunfire, and about 1 hour away from the minaret of Jam a freshly charred car, with at least one corpse inside, convinced the driver, that the region was off-limits.

The impressive but dilapidated minarets of Herat Mosque

The road between Herat and Kandahar is so dangerous that again – no driver was willing to go there. Consequently, yet again a flight to Kandahar had to be taken. Kandahar was the exact opposite of Herat. A largely Pashtun city, outside the airport, (where IC 814 was hijacked to) – security was intense, the population was visibly hostile to such a degree that even mere requests to talk (and the realisation I was not an afghan), brought angry rebukes. The word “Hindustan” carries absolutely no magic here. The problem escalated rapidly – at an army check post we were informed that there was already radio chatter of an Indian in town and it was best if said Indian left. I was without delay deposited back at the airport thereafter. This was particularly problematic as I had two further meetings with higher Taliban officials lined up and necessitated staying longer than expected at Ghazni where some of the Taliban agreed to travel up to.

A short flight back to Kabul, we had to drive a day later to Ghazni. While I had intended for Ghazni to be a tourist stop, specifically to research Mehmud of Ghazni, the Taliban in Kandahar had warned me against making myself conspicuous and I had been sharply upbraided for attempting to interview locals in Kandahar as a dead giveaway. Consequently, photography and interviews in Ghazni were banned, as it turns out the city is more dangerous than Kandahar for visitors.

Author atop a destroyed soviet BTR outside the town of Ghazni

Ghazni is a truly grotesque city. It has not an iota of beauty and the architecture – military or religious is crude without any redeeming features. It was here in a particularly nasty safe house over the next 2 days that I met a variety of Taliban commanders. There was no verifying their identity or rank, except to take them at face value since their bona fides had been vouched for by Pakistani interlocutors. Yet surprisingly (and this was a theme throughout Afghanistan) there was nothing but pure undiluted hatred of Pakistan. Several claimed they had family in Pakistan – effectively hostages to ensure compliance and yet again the standard theme was that there was no “national cause” here. One particularly curious story was from someone touted as a local commander near the Dutch base in nearby Oruzgan but formerly operating in Gulistan. He was upfront about how they never attacked Italians as the local Italian commander was happy to pay him in cash and medicines, but that when he moved to Oruzgan, the Dutch deployment there refused to do any such thing. (Several Taliban interviewed in Nangarhar, Samaghan, Balkh and Nuristan related similar experiences). It was a vast accumulated set of personal vendettas and grievances tactfully exploited by Pakistan. Government control here is so loose that the Taliban felt safe setting up meetings here and I have no shame saying that the days I spent here were an absolute terror for me not knowing when I’d become “leverage”, so far away from any safety precautions I had taken.

With Sheikh Abdullah (formerly Baktreddin Kakhimov) a Soviet Military

Intelligence officer,who became Mujahidin after his capture in Herat

Gauging the Taliban – Myths and Reality

There are two distinct conflicts in Afghanistan. The first and possibly more deep-rooted, is the endemic rural-tribal vendettas pent up over years and intensified due to the lack of any form of central authority. The second conflict is Pakistan versus the rest conflict, where elements of the first conflict are successfully manipulated to serve Pakistani interests howsoever they are perceived in Islamabad. Indians must understand this clearly. While it does not serve to reduce the potency of Pakistan’s machinations – both the United States and India seem to have made grave errors in how they deal with this duality.

The United States’ primary error was that it decided to engage in “nation-building” imposing bizarre first world paradigms in what is essentially a feudal tribal confederacy – essentially a remnant of the Persianate gunpowder states sans any central authority. It doesn’t exactly take a genius to figure out within minutes of venturing outside Kabul, that dreams like women’s rights, free and fair elections, human rights etc. can only be imposed on the landscape by the extraordinarily foolish. Even rudimentary anthropology should have warned the United States that the only responsibility it had was to create a strong government and leave Afghanistan to its own devices. Europe itself took 300 painful years of social churn to reach where it is. For a loose tribal confederacy, this path would be much longer and more painful – especially after 40 years of unrelenting war which led to a conflict economy.

India for its part seems to have severely erred in its refusal to accept the “good Taliban – bad Taliban” formula. Pakistan has exploited the first conflict to arm and aid anyone willing to take up arms for whatever cause, and frequently agglomerate them into a large potent force capable of overrunning whole provinces. However, these remain fractious and riddled, with Pakistan exercising control only at the very top, through a mix of hostage-taking, carrots and sticks. Given the fluidity of the Taliban with the general rural population and the uniform hatred of Pakistan across the board – India is imposing artificially, binaries that are simply irrelevant or comical on the ground.

Afghanistan is doing what it has always been doing for centuries now. It is not a solvable problem, rather more of a manageable problem. The issue is the questions you ask and the preconceived notions you take seem to end up dictating policy more than ground realities – be it India or the United States. Pakistan does and will continue to exercise significant control over the top echelons of Afghanistan’s feudal strongmen, there is nothing that can be done about it. However, management of the problem dictates that India also exploit the notorious fickleness and duplicity of these feudal strongmen, rather than bunch them up into one consolidated “basket of deplorables”. Realistically, no Afghan state can have a monopoly on violence the way it is understood in modern parlance. But what can be achieved is an Afghan Central Authority – strong enough to prevent larger coordinated eruptions of violence, and to play divide and rule when such coordinated eruptions eventuate.

A large part of the Taliban can be partially pacified (as best as that term can be applied in such a situation) through engagement and that is what this paper deals with. This would also lead to a significant reduction/disruption in the command and control abilities of the Taliban high command. To conclude, India needs to get off its dogmatic high horse.

*******************************************************************************

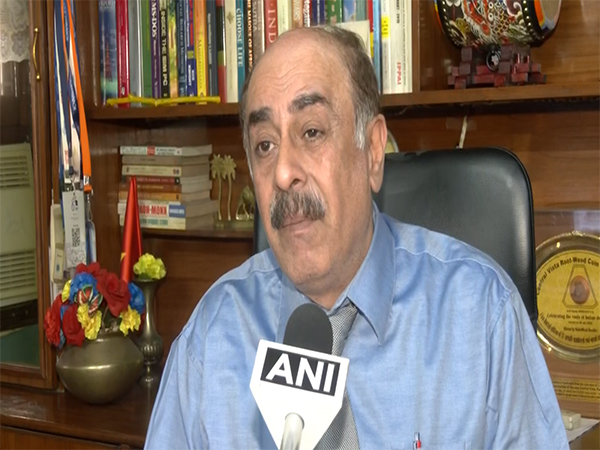

Author

Abhijit Iyer-Mitra is Senior Fellow at the Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies. A Defence Economist, he appears regularly in print and on TV, is the author of two books and doing a PhD at Kings College London.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of Chanakya Forum. All information provided in this article including timeliness, completeness, accuracy, suitability or validity of information referenced therein, is the sole responsibility of the author. www.chanakyaforum.com does not assume any responsibility for the same.

Chanakya Forum is now on . Click here to join our channel (@ChanakyaForum) and stay updated with the latest headlines and articles.

Important

We work round the clock to bring you the finest articles and updates from around the world. There is a team that works tirelessly to ensure that you have a seamless reading experience. But all this costs money. Please support us so that we keep doing what we do best. Happy Reading

Support Us

POST COMMENTS (10)

Sandipan Nath

KARTIKEY MISHRA

Vijay Vidhate

srinivasan k

elizabeth dunn

Myo Nyunt

Saagar

Cdr Sandeep Dhawan

Sangam Singh

Sidharth